Blue day in Detroit

/In the week of the North American International Auto Show - aka the Detroit motor show - we peek into a museum named after a man who made Motown.

SO you know a Fiesta from a Focus, and perhaps can even recite the lineage and provenance of every Falcon, from first bore centre to latest ball joint?

But how much do you know about the man behind the name? Assuredly, you’ll discover a whole lot more from having visited a 102-hectare attraction in the Detroit sub-city of Dearborn.

An area called The Henry Ford is dedicated to the world's largest family-controlled business and the efforts of the pioneer responsible for the iconic Model T, the $5 working day and the first automotive assembly line.

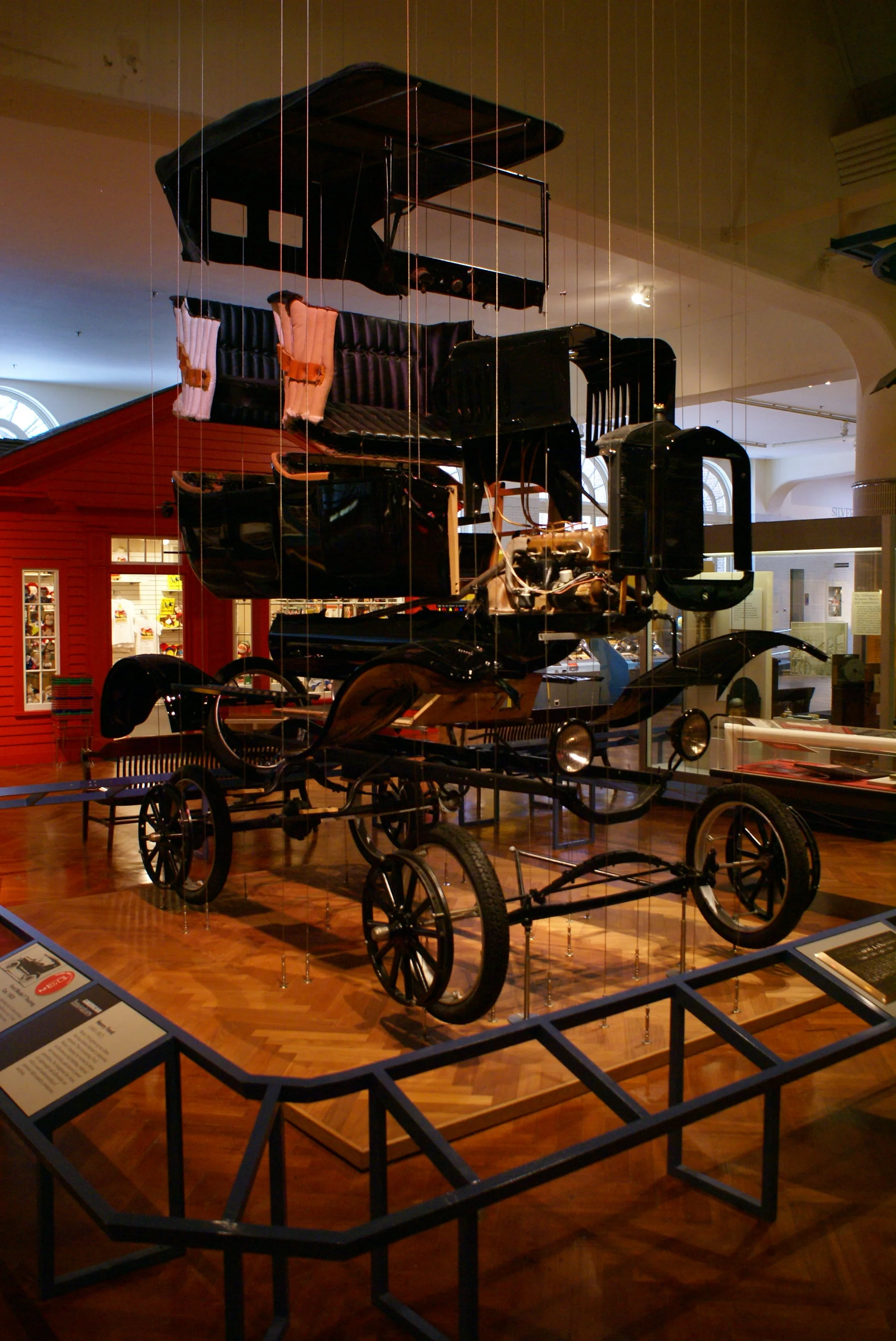

The all-year attraction is a vast museum containing hundreds of historically important vehicles, including the first Ford - the 1896 Quadricycle, and the very first Model T, the car that put America, then much of the world including New Zealand, on the road and made Ford a household name.

But 'The Henry', as it has been known for the past decade, is more than just cars. Or even a museum building.

An equally important part of the property, though closed for winter, is Greenfield Village, a curious concoction of eighteenth and nineteenth buildings put together by Henry I during the 1920s as a tribute to America's past.

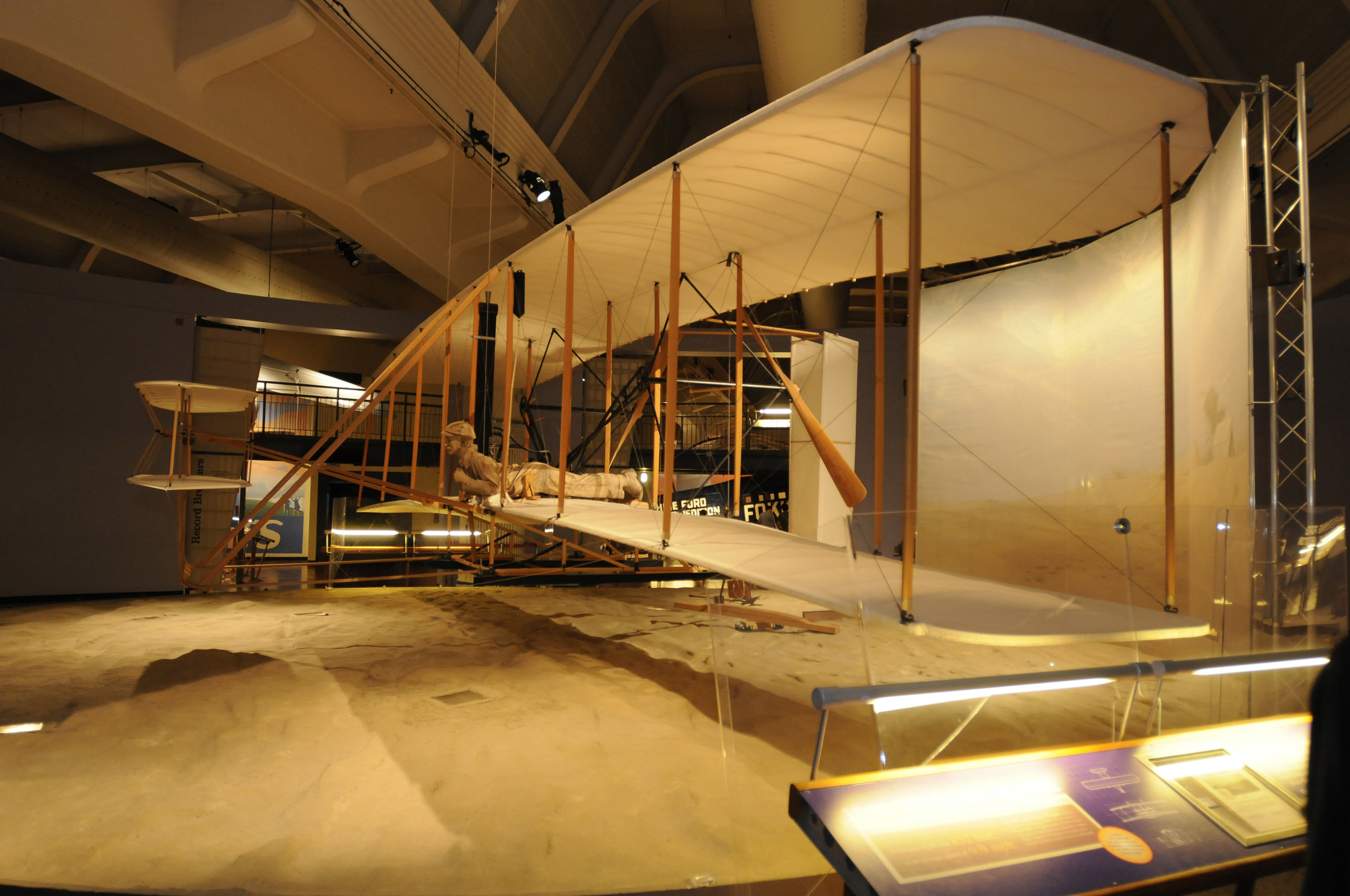

Described by controversial Ford biographer Robert Lacey as "a never-never land as Norman Rockwell might have imagined it", Greenfield preserves the courthouse where Abraham Lincoln practised law, a stagecoach tavern and the Ohio bicycle shop where the Wright brothers built their first flimsy aircraft. It is both a wondrous, slightly weird and very particular reconstruction inspired by the man whose most famous saying was "history is bunk."

The third part of this facility is the Rouge, the factory that produced most Ford cars and is still knocking them out, though the output rate is vastly lower than during Motown's heyday. Even so, the vast looming mass of the River Rouge plant still makes awesome impact in a town that still congregates more car makes than any other spot on Earth.

The world's largest industrial site when it opened in 1918, the Rouge was the place that realised Henry's vision of creating cars from raw materials, rather than simply putting pre-prepared bits together as rivals did.

Epitomising the genius of mass production, The Rouge consumed vast quantities of coke and ore from Ford mines, raw rubber (some from Fordlandia, a failed plantation in Brazil) and timber from Ford forests. It popped out cars by the million. The T, the Model A, the Thunderbird and Mustang … all, and so many more, were from here.

Actually, the Ford influence over Detroit goes beyond 'The Henry.' The most famous four letter word in the car world is everywhere in Detroit.

My late night drive in from the snow-covered airport was on the Edsel Ford Freeway (in a Ford of course).

In the inner part of the city that once symbolised the American Dream – and has more latterly been so wracked by urban decay that many grand buildings lay empty and uncared for - you will find Ford Auditorium, Ford Road, Ford Hospital.

But only if you wanted to. Downtown Detroit is no place to be. When I visited for this story, seven years ago, the home of the Big Three - Ford, GM and Chrysler - that once boasted the highest median income and home ownership rate in the US was in what many commentators were then calling a 'death spiral.'

The school system was in receivership and in the month prior to my 2010 visit, the city treasury admitted it was $NZ414 million short of the funds required to provide basic services.

The jobless rate ran at 28 percent, higher even than during the worst years of the Depression. People were angry and in a dangerous mood. I was told the murder rate then was high enough to make an evening stroll seem like a suicide mission.

All that seemed a million miles away when I was at 'The Henry.' Here the layer of nostalgia is thicker than the grain-fed steaks they served up at our hotel, a 1930s mock Tudor ... designed by Henry Ford.

I’ve been to the museum twice; this being my second visit. In 2010 it was undergoing a massive revamp, which seemed an ironic twist when Detroit was so patently falling further into decay.

In original state, it was stark and austere. "A vast, humourless collection amassed by a vastly humourless man," one critic put it. The place when I last saw it was well on the way to being transformed by the forces of pop culture and light into something that did much more to enoble, with a slight sense of fun, the car culture that made this city.

There are Ford cars in abundance, but only from this side of the world. Look in vain for Aussie and English/European Blue Oval bangers. Yet there is a 1984 Honda Accord. Curious.

Historically important vehicles abound. The four presidential limos include the Lincoln John F Kennedy was riding in when he was assassinated in Dallas in 1963 and an earlier edition that would have made his predecessor, Dwight D Eisenhower, an equally easy target.

It has a plexiglass roof, hence the nick-name 'the bubbletop.' Not only did the group I was in get see the 1972 Lincoln that Ronald Reagan rode in but also, by chance, got to meet a Ford employee who helped design it. (Ford fact: The car cost around $US3.7 million to create, but was 'sold' to the US Government for $100,000).

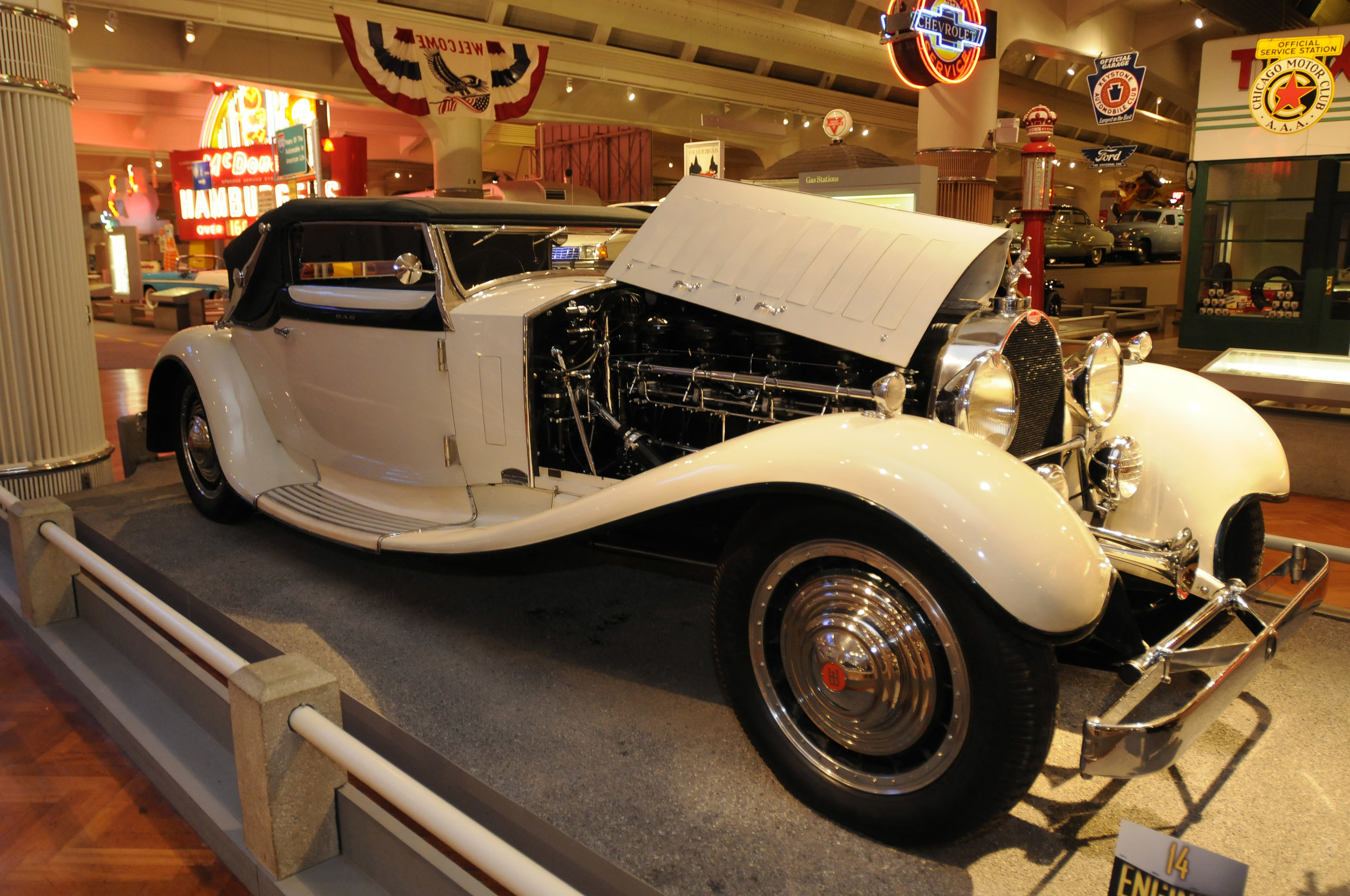

There's an Edsel, one of the few 1948 Tucker sedans produced, the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile (surely you know that's a car made to look like a hotdog?), and one of the world's six Type 41 Bugatti Royales, a 1931 cabriolet that was rescued from a junkyard. As a wreck, it was worth $US800. In 2007 it was valued at $US20m.

There is the Mustang concept of 1962 - if you ever wondered where Mazda got inspiration for the nose of the orginal RX-7, here it is - and the even more iconic production car. The white Mustang convertible was the first off the line and used to be driven by Lee Iacocca.

There are historic racing cars in the Ford GT MkIV that Dan Gurney and AJ Foyt took to victory at Le Mans in 1967, a year after Chris Amon and Bruce McLaren first cracked the 24-hour (their car is at the Indianapolis 500 Museum) and the 1902 999 racer. The Goldenrod land speed record racing car of 1965 sits in a corner.

Full sized dream cars include Ford's X-100 50th Anniversary model from 1953, with an electric shaver, a dictaphone an electronic jacks as standard equipment.

There's another vehicle that made even bigger history. The bus on which a quiet black woman, Rosa Parkes refused to give up her seat to a white man, an event that triggered the Civil Rights movement and the transformation of a whole nation. The bus came to the museum in 2000, bought at auction for more than $400,000 from a man who had it mouldering in a field. As much again was spent on the restoration.

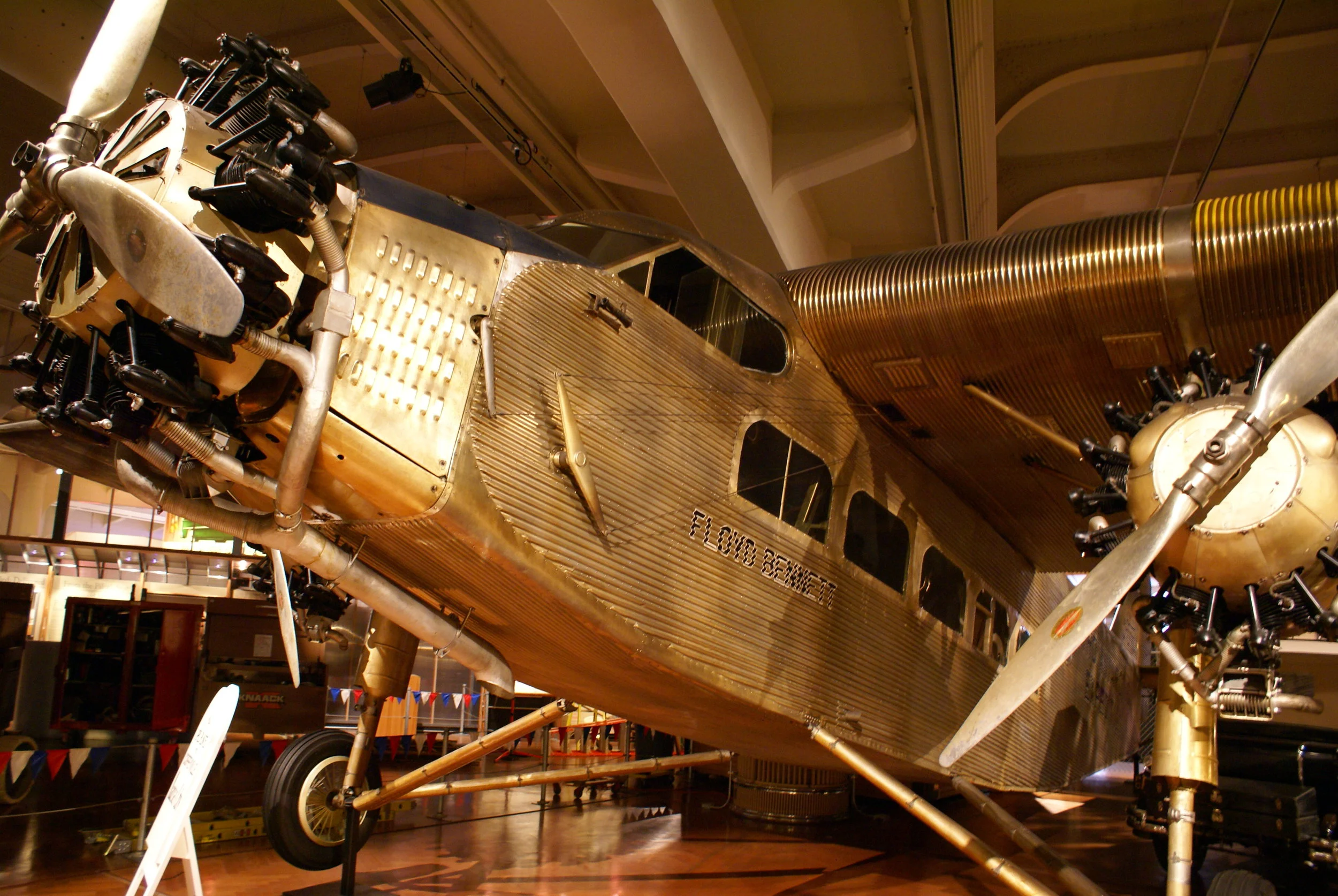

Another area features airplanes (personal favourite, the Ford Tri-Motor) and biplanes, including those with Ford's Tri-Star engine. There are long lines of big steam engines dug into the floor (so that their flywheels will fit) and huge locomotives, including the world's biggest (1941 Allegheny).

Also here are the original neon restaurant signs from McDonald's and Howard Johnson's, a Holiday Inn hotel room, and a Texaco Gas Station. High ceilings shelter a whole 1946 roadside diner, complete with a live human waitress, on duty to dispense museum information, not food sadly. Back in '46, a chicken salad cost 25 cents.

Henry Ford collected all sorts. A "Made in America" display explores the legacy of other mechanical devices that also changed the way we live, from the toaster to the locomotive. You can look at a hall of furniture and old office machines - okay, I didn't - and even, er, a fats and resins display.

Even the museum is a prized exhibit. The exterior was modelled on a key US state building in Philadelphia, to the extent that it has the same design flaws as the original. The floor comprised exact-sized tongue and grooved (so no nails) pieces. Advised to use teak because it was the hardest-wearing timber, Ford bought up the world's supply for two years.

Henry Ford proclaimed that this museum, which opened in 1929, would show how the inventions of a few (mainly Ford and his industrialist pals) had forever changed America. The artefacts of Harvey Firestone, Luther Burbank, and Thomas Edison (including his last breath, in a test tube) are here. Their historic homes make up much of The Greenfield Village.

Ironically, the one story it doesn't tell is about the man who started life as a Michigan farmboy and rose to run one of the world's largest and most respected companies.

(This story first appeared in Top Gear New Zealand magazine. It has been amended since).