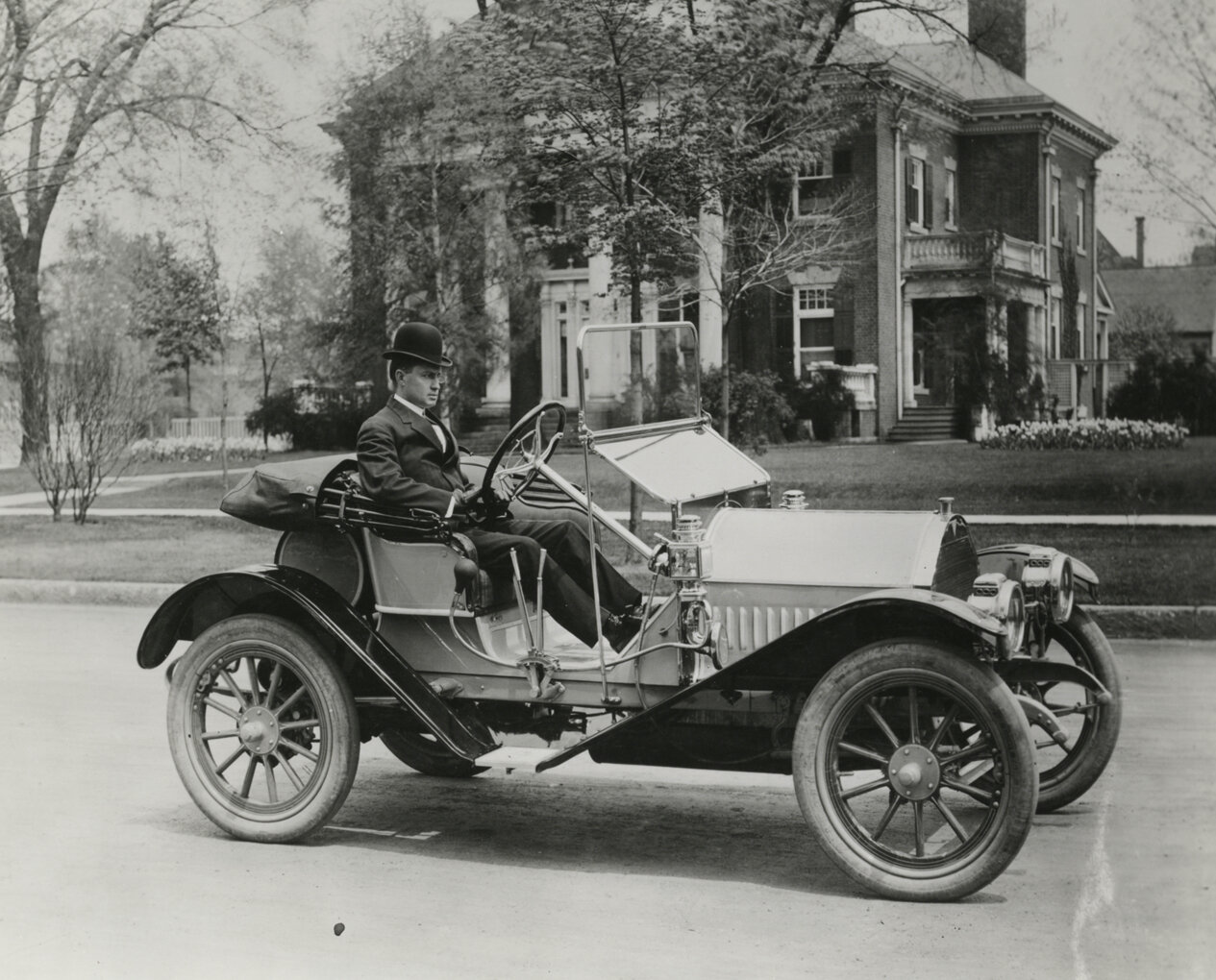

The man behind Hudson

/Roy Chapin was instrumental in the expansion of the American automobile industry.

ROY Dikeman Chapin was one of those inexhaustible men who seem to wring 48 hours out of every 24 hour day.

His tragic death from pneumonia in 1936, at the age of 56, ended an utterly amazing and diverse career that spanned the automotive industry, highway development, politics and banking.

Born on February 23, 1880 in Lansing, Michigan, Chapin attended the University of Michigan where he studied business. In 1901 he accepted a position at Olds Motor Works but most of the work was initially menial that had little to do with his areas of expertise. For $35 a month his primary tasks were take publicity photographs, run errands, and file gears. Still, Ransom E. Olds was an excellent teacher and had an eye for recognizing untapped talents. Chapin was an eager and observant student.

During his five years with the company Chapin rose through the ranks, learned about automobile manufacturing, marketing, labour management, financing and distribution. In 1904 he became the company’s national sales manager.

A career changing event for Chapin took place in 1901 when Ransom Olds asked him to drive one of the new curved dash Oldsmobile cars to New York City for the second annual Auto Show. The grueling 820-mile trip took a full week to complete. Rutted, rocky and muddy roads, and in some rural areas a scarcity of gasoline, proved to be major obstacles to overcome.

Still, the trip which proved the mechanical prowess of the car brought much fame and recognition to the “Merry Oldsmobile” which was priced at $650. And this fueled a meteoritic rise in sales from 425 vehicles in 1901 to 2500 in 1902. By 1904, Oldsmobile was the largest manufacturers of automobiles in the United States.

The adventure made Chapin a subject of interest for journalists and provided networking opportunities with manufacturing pioneers. And this adventure also played a pivotal role in his work with the establishment and development of good roads associations that commenced in earnest in 1904. His crowning achievement in this endeavor was an association with Henry B. Joy of the Packard Motor Car Company that spearhead construction of the Lincoln Highway, the nation’s first coast to coast automobile highway.

One of Chapin’s greatest attributes was diplomacy and his ability to move fluidly between competing entities without recrimination or lasting animosity. When the Smith family, majority shareholders in the Olds Motor Works, and the companies’ founder, Ransom E. Olds reached an impasse about what direction to pursue, Chapin maintained a long an amicable friendship with both parties even after Olds left his namesake company and the Smith family promoted him to general manager.

His diverse contacts in the automotive industry and in media, and skills honed during his tenure at Olds Motor Works were the foundation for his next automotive endeavor, the development of Thomas Detroit. But this as well as his work at Chalmers Detroit were merely a stepping-stone on his path to automotive tycoon.

In 1909, with the partnership of former Olds Motor Works alumni George Dunham, Roscoe Jackson, and Howard Coffin, and with financing from department store magnate Joseph L. Hudson, Chapin launched his greatest automotive venture to date. The resultant Hudson Motor Company would quickly become an industry leader in technological development, and by 1929, one of the nation’s largest automobile manufacturers.

Aside from taking an active role in the management, engineering development and marketing of Hudson, Chapin was also serving on the executive committee of the Lincoln Highway Association and writing feature articles about the importance of a nationwide system of all-weather roads and the how the automobile was enhancing American society for numerous publications including the Saturday Evening Post. And he traveled extensively to promote Hudson as well as the work of goods roads associations.

Chapin steered the Hudson company from its infancy, through the post WWI economic recession, and ensured that the company was an industry leader in the areas of production as well as technological development. He also was instrumental in the launch and development of the Hudson Super Six in 1916, and the Essex line that included the industry leading Essex Coach. Edsel Ford noted that the coach transformed the buying habits of the consumer from seasonal to all year round and credited this car for record winter sales throughout the industry.

Few things attest to Chapin’s remarkable ability to maintain long-term relationships with business associates than the one that he shared with the Ford family. With Edsel, he developed a close friendship as well as business relationship and with Henry, he earned a grudging respect. He also retained a friendship with Ransom E. Olds, and a working relationship with Charles Nash, Walter Chrysler, and other leaders in the auto industry.

A blemish on his record for integrity resulted from his association and managerial position with the controversial Guardian Group, a complicated investment vehicle consisting of banks, holding companies, and automotive finance entities established in the mid-1920s. He and others involved in this endeavor included men involved with the direct management of Oldsmobile, General Motors, Chrysler, Ford, Studebaker, and as well as leading Detroit and Chicago banks. There were also questionable political associations.

With the dramatic stock market collapse in October 1929, and economic contraction that commenced in earnest in 1931, the Guardian Group became intertwined with the collapse of banks and resultant of loans, stock dumping, and practices, pushed several automobile manufacturers into receivership or bankruptcy. In 1932, Chapin relinquished his management position at Guardian Group and accepted an offer from President Hoover to fill the vacated position of secretary of commerce. His almost unanimous approval for the position indicates the level of respect he still commanded despite an ongoing investigation of corruption in Guardian Group.

With the election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Chapin returned to Detroit and resumed his managerial position at Hudson, a company on the very brink of collapse. The company’s slide had begun in 1931 as reflected in a loss of almost $2 million and a precipitous 85 percent slide in manufacturing. The red ink continued to flow through 1932 and in 1933. With losses of $4.4 million, suppliers threatening legal action, a bank loan of $8 million overdue, and Commercial Investment Trust hinting it might refuse to further finance Hudson’s new car sales the company was in a precarious position.

Through Herculean efforts that involved restructuring, extensive international travel to facilitate diverse partnerships, and complicated negotiations with labor as well as banks, Chapin miraculously restored the company to solvency in 1935. This was also the year he resumed his position of spokesman for the auto industry, a position that included representation and lobbying in Washington D.C.

The Chapin story ended abruptly in February of 1936 with the death of an independent thinker of epic proportion. What a man of this vision, of this ambition could have accomplished for Hudson, as well as the nation is left to speculation.

Written by Jim Hinckley of jimhinckleysamerica.com