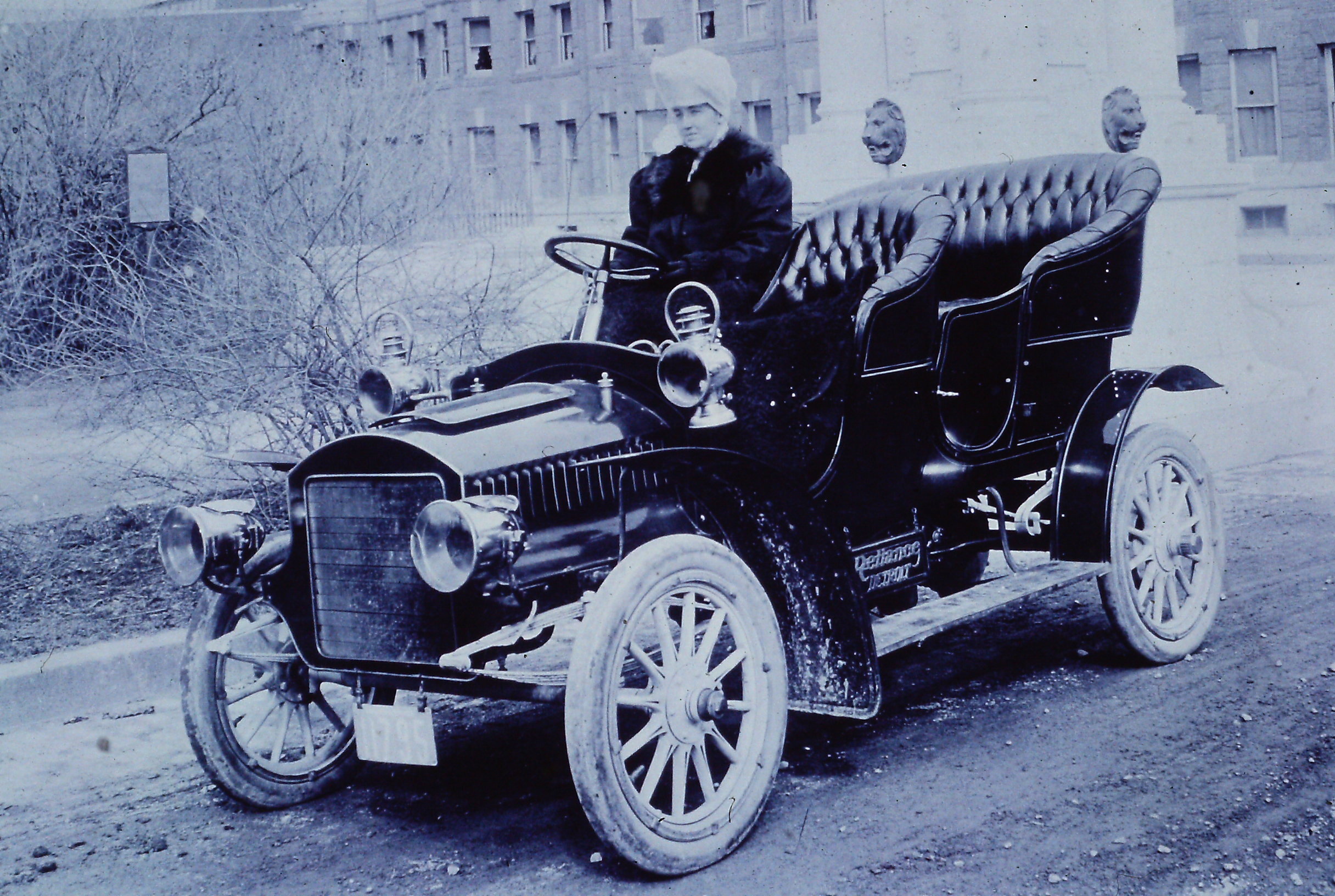

Henry Leland: The genius of precision

/He came into the automotive industry late in his lifetime, but in that short span of years founded two of America’s most storied automotive brands.

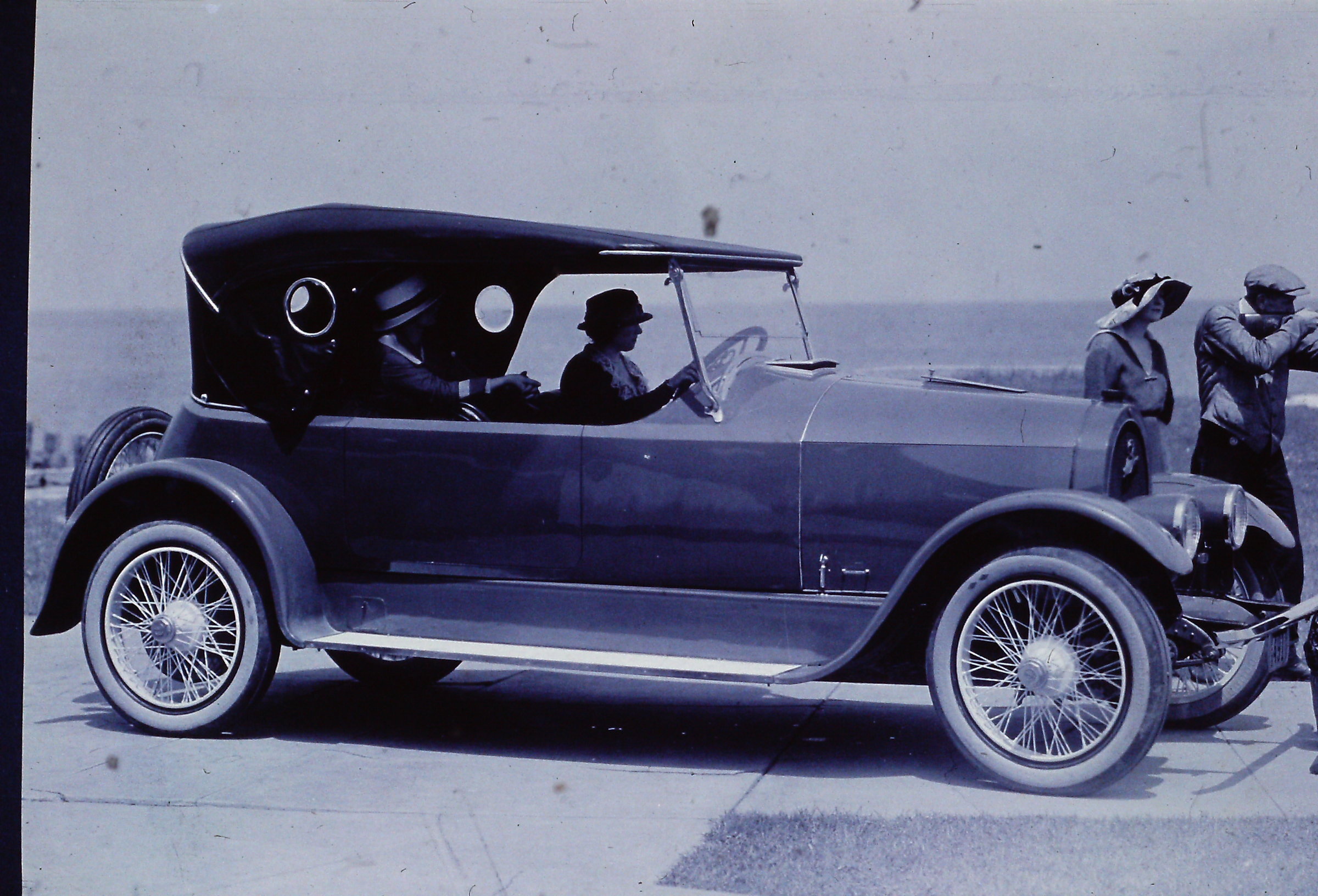

A 1922 Lincoln … the brand was renowned as a producer of well-crafted luxury product.

“THERE is a right way and a wrong way to do something. Hunt for the right way and then go ahead.”

That was a favourite saying of Henry Leland, a truly gifted machinist, a mechanical engineer with vision and an obsessive perfectionist. It was a winning combination during the dawning of the American auto industry.

Born in 1843, Leland earned engineering degrees from the Universities of Michigan and Vermont and studied precision machining in the Brown and Sharpe plant at Providence, Rhode Island and Colt, the firearm manufacturer.

During the American Civil War, he worked as a toolmaker in the United States Arsenal. His first forays as an inventor, first with electric barber clippers and then with a unique toy train, the Leland-Detroit Monorail proved financially lucrative.

In 1890 Leland moved to Detroit and established Leland and Faulconer Manufacturing Company to build marine and stationary engines. The company soon established a reputation for quality, innovation, and precision engineering, and by the turn of the century, was also making engines for automotive application. Counted among the company’s ardent supporters was Ransom E. Olds, who had hired the company to design an engine for the Olds in 1902.

By the dawning of the new century Leland found himself embarking on a new business endeavor as financiers and bankers retained his services to appraise the assets of moribund companies that manufactured automobiles and automotive components. In 1902, he was hired to appraise the assets of the Henry Ford Company and to create a plan for making the company viable. The company namesake, Henry Ford, was incensed and left the business taking several partners with him. Leland seized the opportunity.

A devastating fire at Olds Motor Works had led to termination of his arrangement with that company. It also left him with a single cylinder engine designed for automotive application.

After appraising the company’s assets, he suggested that the investors should reorganize, use the chassis designed by Henry Ford and the engine Leland had designed for Oldsmobile. Hoping to cut their losses, and perhaps even turn a profit, the investors agreed. The new company was named for Cadillac, the French explorer that had established Fort Detroit.

Leland established unprecedented manufacturing principles that soon became industry standards. He and Ransom Olds had used interchangeable components on several vehicles but on the 1907 models of Cadillac, Leland took the concept of uniform parts to an entirely new level. The idea had originated with firearms manufacturing. Eli Whitney had displayed the advantages of interchangeable musket parts at an exhibition before the president of the United States in 1801.

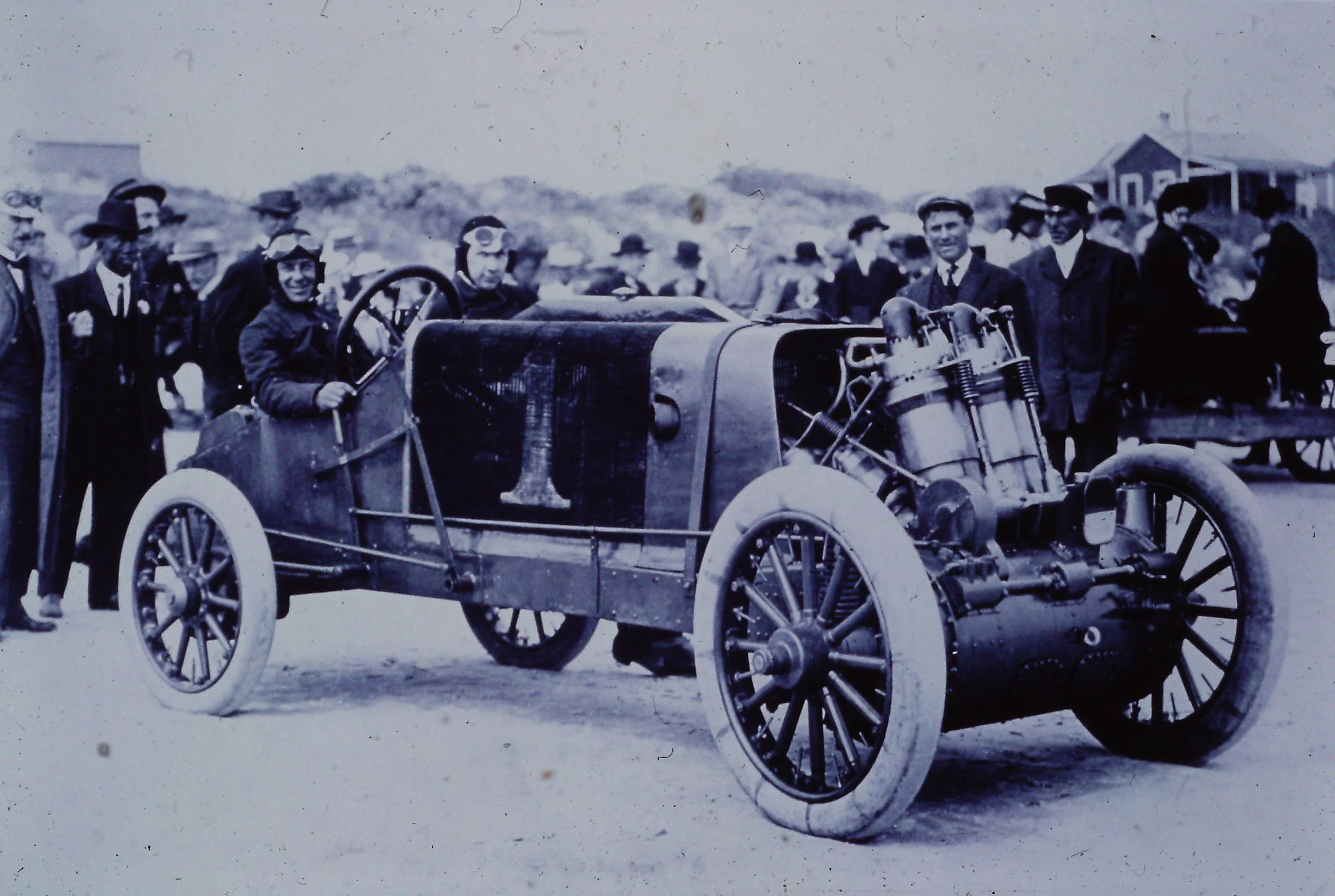

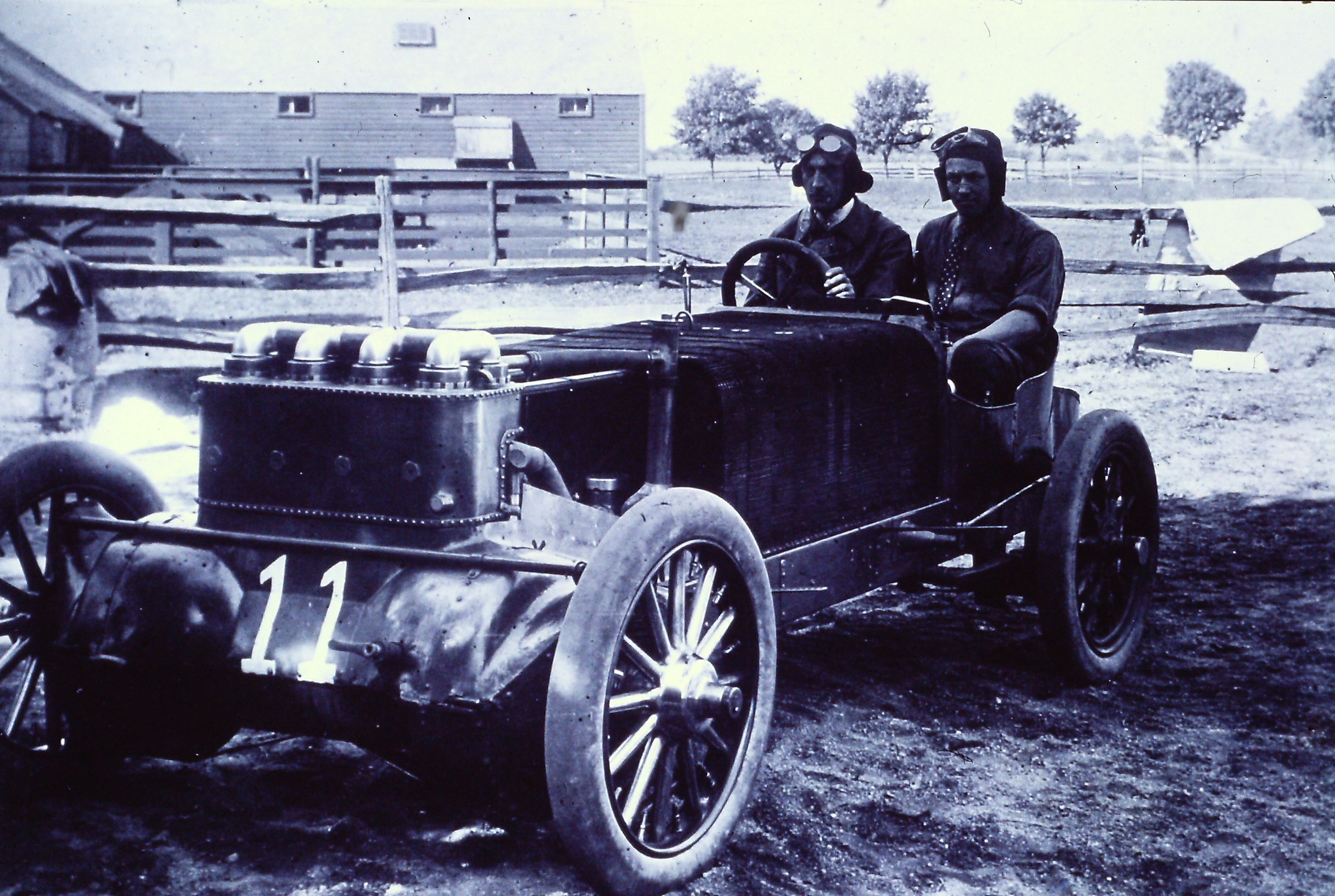

On Saturday, February 29, 1908, three Model Ks were randomly selected from the stock of the Anglo-American Motor-car Company, the British agent for Cadillac automobiles. The three cars were driven 25 miles to the Brooklands racetrack and then completed 10 laps of the track, approximately 30 miles. Under strict supervision the cars were locked away until Monday, March 2, 1908. Then before an audience of reporters, mechanics, engineers, automotive enthusiasts and automobile agents, the cars were displayed and fully disassembled. Each car was reduced to a pile of 721 component parts that were scrambled into one heap. Next Cadillac mechanic E. O. Young began reassembling the cars with the help of his assistant, M. M. Gardner. By Thursday morning, March 12, the third car was completed. The following day they were all driven 500 miles.

On completion of this test, one of the cars was locked away until the start of the 2000-miles reliability trials in June, 1908. That car finished in first place and was awarded the R.A.C. Trophy for its class. Cadillac was deemed the Standard of the World.

In 1910, Leland began working with Charles Kettering to develop an improved electrical system. Two years later Cadillac became the first company to offer an electric starter and lights as standard equipment. But the company had been acquired by William Durant in 1909, and folded into the General Motors combine, and that proved to be a turning point for Leland’s association with Cadillac.

Durant had an abrasive and overbearing personality that had become his trademark. In late 1916, after a heated discussion about Durant’s refusal to accept a government contract for the manufacture of aircraft engines, Leland left the company. In the years that followed, Charles Nash, Walter Chrysler and others would also leave General Motors after disagreements with Durant.

And so, Leland and his son Wilfred formed a company for the manufacture of Liberty Aircraft engines in 1917. It was named for the first president Leland had cast a vote for in 1864, Abraham Lincoln. As testimony to Leland’s reputation he received the government contract to produce 6000 engines without review. But before full production could commence, the Armistice was declared, and the contract voided. This left the Leland’s deeply in debt and with a huge factory as well as a workforce of nearly 6000 men.

And so, the decision was made to shift to automobile manufacturing. Again, Leland’s reputation proved to be a valuable commodity as the initial $6.5 million capital stock offering for Lincoln Motor Company sold in less than three hours. Without a single car being produced, trade journals and automotive journals praised the Lincoln based solely on Leland’s plans for the vehicle.

Leland’s obsession with detail and extensive testing resulted in a near continuous string of delays. As a result, the new Lincoln debuted in September 1920 amid a severe economic recession and nine months after the cars planned release. Mechanically it was a technological masterpiece, powered by a 60 degree V8 engine. Seventy mile per hour speeds were guaranteed. Innovations included circuit breaker electrical system, full pressure lubrication, thermostatically controlled radiator shutters, and a sealed cooling system with condenser tank. Prices ranged from $4500 for the Town Car to $6000 for the roadster.

The cars mechanical prowess was proven almost immediately. In April 1921, a Lincoln was driven to a first-place finish in race from Los Angeles to Phoenix. The second-place finisher arrived almost an hour later. But technological advancement, performance, and ecstatic press was not enough to overcome the delayed debut and the resultant company debt, the economic recession, the high sales price and dated styling. A mere 674 cars were sold in 1920, and 2800 in 1921.

In November 1921, the company was forced into receivership. As a touch of dark irony, the company was acquired for $8 million dollars by Henry Ford. The Leland’s were retained as consultants, and Edsel Ford was installed as president. It proved to be a short association as the company’s founders left within four months and initiated litigation to force Ford to reimburse original creditors and stockholders.

Leland’s last act was pure class. In 1931, as the ongoing legal battle with Ford continued, he wrote letters to the former stockholders, parts suppliers, and investors, and personally apologized for the fact that Ford had not compensated them as promised. He died in March of 1932.

It was truly the end of an era. Leland’s career had spanned the period between the beginnings of the industrial age to the mass production of automobiles. He had made contributions to manufacturing, to the automobile industry, to barbershops, to children’s toys and to business management. He had launched an automotive empire that would come to symbolize prestige and luxury. Leland’s contributions transformed our world.

To read more by Jim Hinckley go to jimhinckleysamerica.com