The glory and tragedy of the Dodge brothers' story

/The death of the Dodge brothers marked the end of an era and sent shock waves through the American auto industry.

THE implications of the Spanish Flu pandemic that began its relentless march around the world in 1918, much like COVID 19 today, were far reaching.

While at the National Automobile Show in New York City in January 1920, both John and Horace Dodge became sick. There is still some debate over their illness but at the time the consensus was that they had been infected with the last wave of the devastating Spanish flu pandemic that killed more than 50 million worldwide.

As with many victims of COVID 19, on January 14, mere days after becoming ill, John was afflicted with pneumonia and died in his hotel room at the age of 55. Even though he suffered from cirrhosis of the liver, the official cause of death, Horace recovered from influenza and pneumonia but was nearly bedridden for most of a year in Florida before dying on December 10 at the age of 52.

The death of the Dodge brothers marked the end of an era and sent shock waves through the American auto industry. It also brought an end to plans to revolutionize the industry from manufacturing to sales and marketing.

The brothers epitomized the American dream of rising from humble beginnings to vast wealth. They were rough and tumble, hard drinking blue-collar men from Niles, Michigan.

John Francis was born in 1864, Horace Elgin in 1868. Their grandfathers, father and uncles were machinists. Both were mechanically inclined. John was somewhat reserved; Horace developed a reputation for a hair trigger temper. Together the redheaded Dodge boys were an inseparable team.

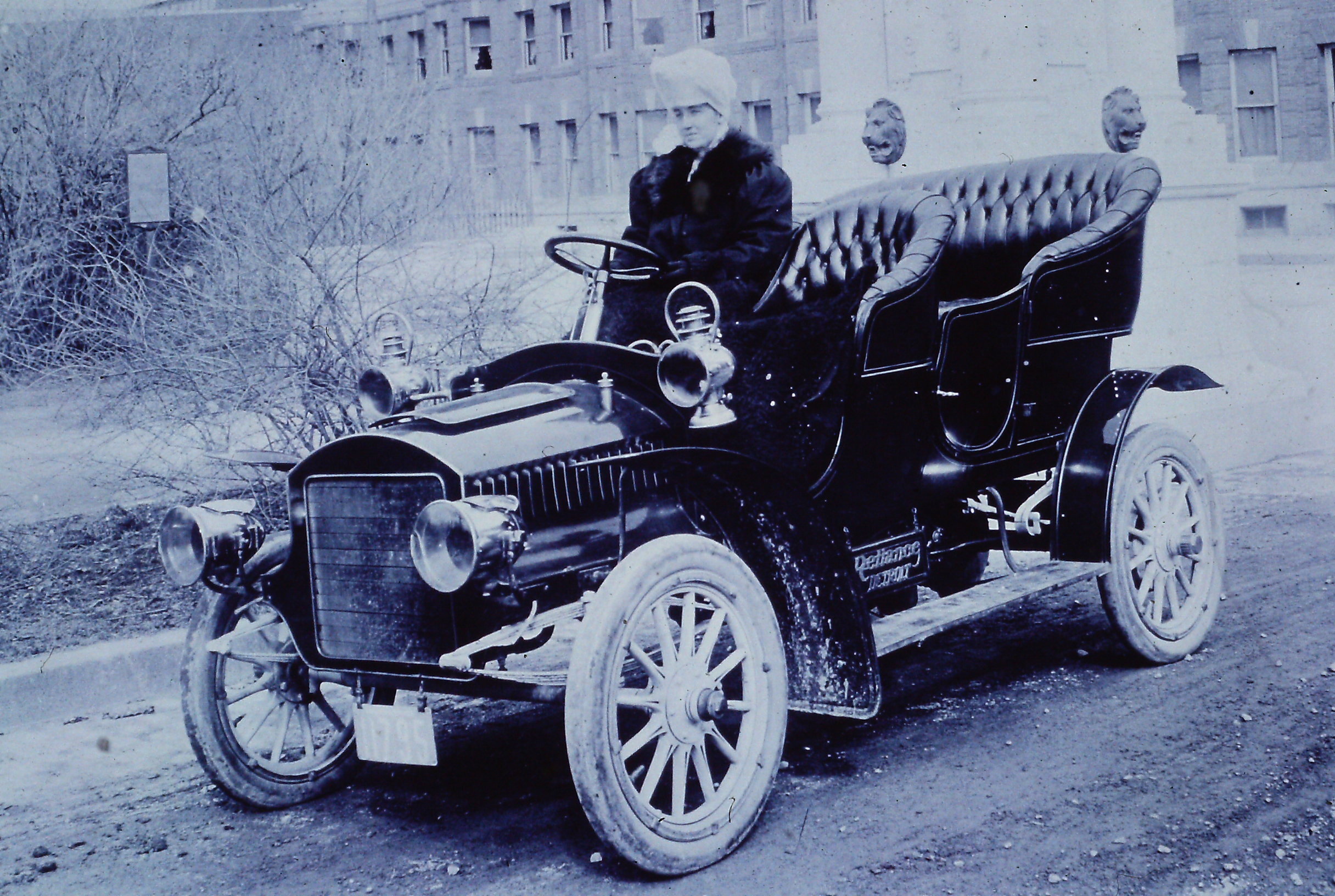

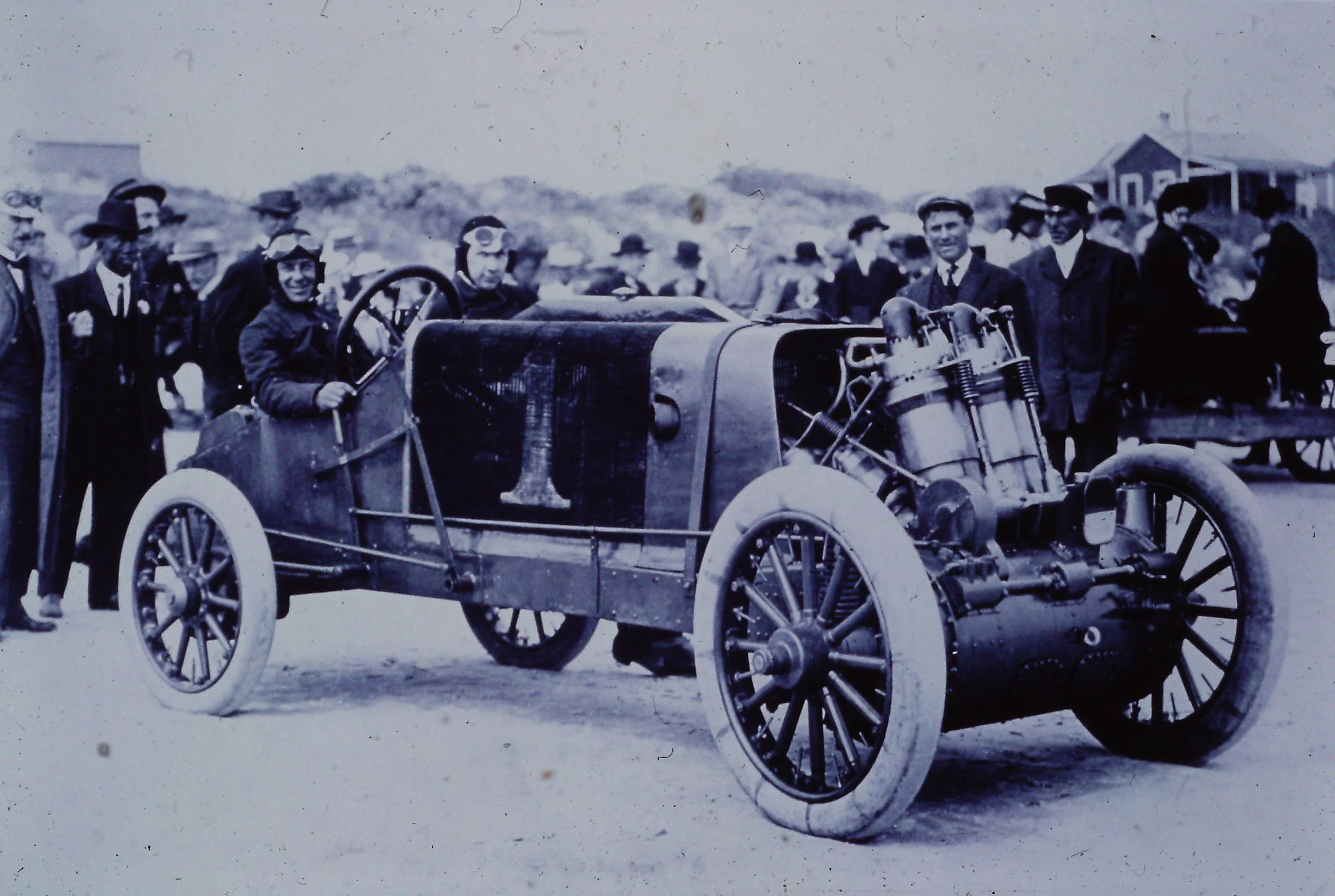

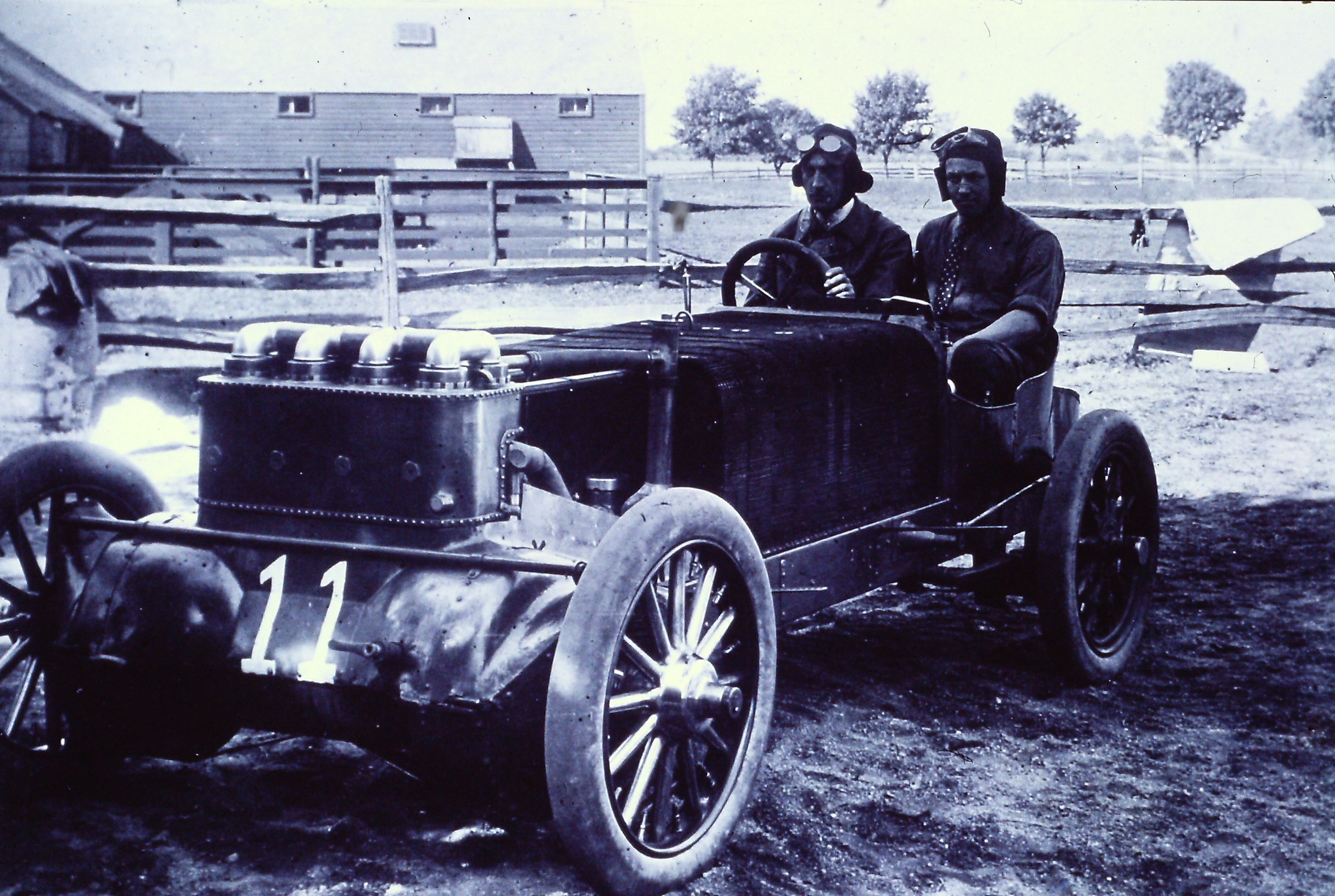

The brothers never were able to move beyond their brusque blue-collar ways even with the acquisition of tremendous wealth. In 1910, the Detroit Times enhanced their reputation as brawlers with an article that detailed a wild bar room fight. John Dodge responded by first publicly apologizing to the bar owner and then paid for damages. He then threatened to kill the paper’s owner. Horace once beat a man unconscious in the street after he made fun of him for being unable to crank his Ford. The brothers were known throughout the Detroit area, as well as in Chicago and New York City, for hard drinking exploits while wearing identically tailored suits and speedboat racing.

Even though they were counted among the wealthiest men in America, they were excluded from Detroit high society. So, when the Grosse Pointe Country Club wouldn’t admit him, Horace built an enormous mansion on the adjacent property, with a 12-car garage and testing facility that faced the country club. They also funded the Detroit Symphony and led the effort to build their Symphony Hall.

The brothers began making their mark in Detroit almost as soon as John moved to the city in 1886. The following spring Horace joined him. The brothers were bright, ambitious, and hardworking, and soon John was earning $16.50 a week as a foreman and Horace $13.50 as a machinist in a boiler manufacturing company.

In 1892 they began working for an equipment manufacturer in Windsor on the Canadian side of the Detroit River. They also developed a ball bearing bicycle, the Evans and Dodge Bicycle, in the hope of profitably tapping into the tsunami of interest in the two wheeled transportation phenomena. In 1900 they established their own machine shop in Detroit. They placed an advertisement in the city directory that mirrored their confidence and ambition, “we are prepared to do any class of work that can be done in a first-class modern shop."

They soon established a reputation for quality work and within one year had secured a contract from Ransom E. Olds to supply engines for his fledgling Olds Motor Works. The brothers began supplying transmissions for the company six months later. In February 1903, the second major contract was secured. This time the customer was Henry Ford who retained their services to manufacture the running gear for his forthcoming Model A.

As this was Ford’s third attempt to launch an automotive company, and as he had a reputation of being pursued by creditors, the Dodge brothers entered the agreement with concerns that were made manifest a few months later. In June 1903, with Ford owing the brothers more than $7,000, they negotiated an arrangement that would change their lives and the course of the auto industry. They agreed to write off overdue payments and extend Ford an additional $3,000 in credit, due in six months, in exchange for ten percent of Ford Motor Company stock.

For a decade, the Dodge Brothers worked almost exclusively for Ford, and John Dodge accepted a position as vice president of the company. By 1910 their production facilities had become a bottleneck and so they opened a massive, state of the art factory complex in Hamtramck, an enclave surrounded by Detroit.

By 1913, the Dodge brothers had 2,500 full time employees and were the largest supplier of automotive parts and components in the United States. It had been a meteoric rise and the brothers were wealthier than could have been imagined when they moved to Detroit. But as John Dodge once quipped, “I'm tired of being carried around in Henry Ford's vest pocket.”

And so, the brothers initiated an ambitious 18 month plan that included suspension of their agreement with Ford, additional factory expansion, designing an automobile, and purchasing the machine tools needed for manufacture. Dodge Brothers Motor Car Company, one of one hundred and twenty automobile manufacturers launched that year, was established on July 1, 1914. The initial announcement was made in the Saturday Evening Post in August. This was followed by simple advertising and promotion designed to pique interest. "Dodge Brothers."

Then, “Dodge Brothers, Reliable, Dependable, Sound." were added. There were no illustrations or details. This was followed by carefully selected interviews and press release distribution. "The Dodge Brothers are the two-best mechanics in Michigan … When the Dodge Brothers car comes out, there is no question that it will be the best thing on the market for the money," wrote the Michigan Manufacturer and Financial Record in August.

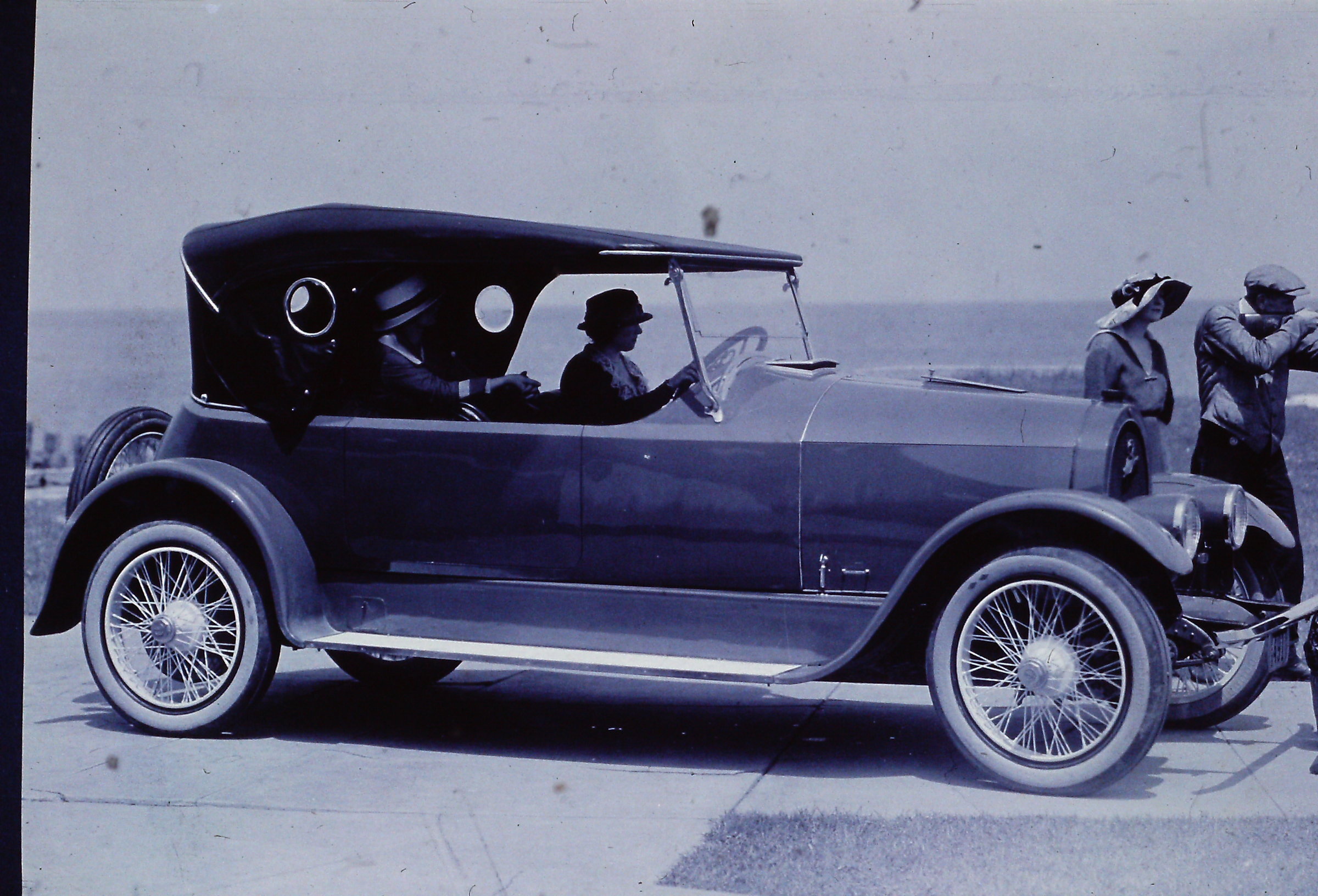

In November, the first Dodge dealership opened in Detroit, and at the debut display of the new Dodge more than 6000 people came to see it in just one day. The five-passenger open touring car was an instant success. It had a 35-horsepower four-cylinder engine with a sales price of $785. A new Ford Model T sold for just $490 but it was rated at only 20 horsepower. And unlike the Ford, the Dodge had as standard equipment an electric starter and lights, a 12-volt electrical system, and a speedometer. The cars were also the first to use an all-steel body. Dodge Brothers manufactured everything for their new cars but the bodies, tires, glass, lights, and batteries.

The Dodge brothers had entered an extremely competitive market. An industry study determined that cars selling for $676-875 accounted for 15.5 percent of the market in 1915 and 19.8 percent in 1916.

There were 15 manufacturers competing in that narrow price range. The Dodge brothers were undaunted. They exported to nearly 50 countries and targeted a multifaceted commercial market that included aircraft companies, communication companies, ship lines, and taxi franchises.

The company was launched with 5000 employees but grew to more than 7000 within a few months. By mid-1919 there were 17,000 men and women working for Dodge Brothers in Hamtramck. Besides Ford they were also the only manufacture to hire African American workers. Other innovations included the first dedicated test track built on the factory grounds.

Like Ford, Dodge Brothers did not make annual model updates. Instead the focus was on mechanical improvements. They also added a wider range of models and commercial vehicles. It proved a recipe for success. Sales soared from just over $US11 million for the year ending June 30, 1915 to $US161 million for 1920. In that same time production had gone from 370 vehicles in 1914 to more than 145,000 in 1920.

In less than 20 years, John and Horace Dodge had built an empire. Then in 1919 their fortunes were magnified exponentially when Henry Ford bought their Ford Motor Company shares for $25 million in cash. This and the dividends cashed over the years gave the brothers a mind-boggling $32 million return on their initial investment of $10,000 in 1903.

One can’t help but wonder what might have been. With the death of John and Horace Dodge, their widows inherited the company. But management foundered without the brothers and in 1925 financial advisors recommended that the Dodge Brothers’ widows sell their interests in the company. Three years later, Walter P. Chrysler purchased Dodge for $170 million in cash and stock options.

Written by Jim Hinckley of jimhinckleysamerica