Testing time for impending GWM H6 hybrid

/How valid is an impressive electric-only range claim when it bases on a disputed test?

Read MoreHow valid is an impressive electric-only range claim when it bases on a disputed test?

Read MoreEmissions, economy returns from Prado, Hilux are improved, if modestly.

Read MoreDropping diesel means less haul in the family; big gun likely topped by Tucson, Palisade.

Read MoreA year on from full implementation, the legislation that set out to wean us from high CO2 vehicles is all but running on empty, with revision pending. While it has helped turn consumers toward electrics, we’re also sticking to the dark side.

Read MoreIt’s a ‘blue’ day with first biturbo Ranger to meet EU6 requirement.

Read MoreWhy is the distance an electric vehicle can travel on a single charge such a big deal?

Read MoreLocal boss says his brand needs to set ambitious goals in its response to climate change.

Read MorePerformance petrol set to land as country ramps up for more change in environmental considerations

Read MoreIs Government reaching too far and acting on poor advice in its intent to deliver world-leading emissions and economy regulations? The organisation representing the industry is increasingly alarmed.

Read MoreSEVERAL legislative amendments tied to Government’s push to clean up vehicle emissions might be impossible to enact in the cited timeframes and will cost consumers and hugely disrupt vehicle supply, Hyundai’s NZ boss contends.

Read More

NZ-new EV availability is ramping up, with this BMW iX (above) among confirmed 2021 entries, but the industry points out that left-hand-drive markets are prioritised, which hurts planning for this country.

NEW vehicle importers support a clean car standard but believe the mooted deadline of 2025 is impossible to achieve and have labelled electric vehicle uptake forecasting as a fantasy.

The Motor Industry Association, which speaks for new car distributors and has more than 44 members covering 81 different marques, is more partial to a 2028 deadline, as suggested in a Climate Change Commission report.

However, it is also particularly scathing of the commission’s considerations about the pace of EV uptake in New Zealand, saying its modelling “enters the realm of fantasy and wishful thinking.”

This is the MIA’s biggest concern, though it is also questioning the agency’s projections about when EVs will achieve price-parity with conventional internal combustion engine vehicles, saying that forecast is also seriously awry. Predictions of low emission vehicles also run ahead of what the MIA believes is possible.

“We consider that the commission’s target of 50 percent of vehicle imports to be electric by 2027 are overly optimistic, as are the projections for price parity.”

It highlights that the world’s EV makers are primarily concerned with meeting demands in markets where hard-and-fast deadlines for reduced emissions and ICE car availability has been established. It also points out that with the exception of the United Kingdom, which plans to ban new ICE cars from 2030, these are predominantly left-hand-drive markets, so as result production for right-hand-drive countries is limited at best.

The Association also believes the commission undervalues the role of carbon sinks, synthetic fuels – that could keep internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles in circulation - and hydrogen technologies.

The latest comment comes after a number of high-profile local distributors, including Toyota New Zealand and European Motor Distributors – which holds rights to all brands held by Volkswagen Group, an electric vehicle production juggernaut likely to overtake Tesla next year (yet is unable to begin supply to NZ until 2023) - have called on the Government for a feebate scheme to sit alongside its clean car legislation, fearing that without it new EVs will struggle to see similar demand.

The MIA’s criticisms and alternate proposals are contained in a comprehensive report responding to the Government having announced, in January, an emissions standard which, if approved, will take effect from next year and also the commission’s subsequent draft report lending opinion about what it believes New Zealand must do.

The deadline for submissions about these matters is today.

The Government’s standard will require new and used car importers to meet incrementally lower emissions targets, falling to 105 grams of CO2 per kilometre average by 2025, from a present average of 171g/km.

The commission has subsequently recommended the Government deploy an end-date for petrol and diesel internal combustion cars, proposing 2032 as appropriate.

In a covering letter to the MIA’s submission, chief executive David Crawford says new vehicle importers supports need for cleaner vehicles, but says the timeline for a lower CO2 average is too rushed.

“Unfortunately the Government’s timeline of 2025 is impossible to reach with resulting penalties becoming a financial impost against all new vehicles including low emission vehicles.”

“Additionally, the transport policies in the draft report focus on vehicles entering the fleet which is only a small portion of the in-service fleet. We need policies to focus on not just only those entering the fleet, but also to target existing vehicles. This will garner a faster rate of emission reductions than just focusing on vehicles as they enter the fleet.”

Additionally, the transport policies in the draft report focus on vehicles entering the fleet which is only a small portion of the in-service fleet, he says.

“We need policies to focus on not just only those entering the fleet, but also to target existing vehicles. This will garner a faster rate of emission reductions than just focusing on vehicles as they enter the fleet.”

In an executive summary, the MIA says the commission should have been “more technology agnostic, and not favour one technology over another, but enable the transport industry to develop innovative solutions” to meet reduced CO2 targets.

Crawford says the commission’s thought that technological breakthroughs will be crucial to enable the agricultural sector to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions does not give consideration to the potential for new technological breakthroughs for the transport sector.

David Crawford.

“The MIA believes the (commission’s) draft advice report needs to give greater weight to the role that synthetic fuels (including e-fuels) could play in reducing emissions from the current ICE fleet.

“ ….we also consider the report has underplayed the potential for hydrogen propulsion, not only for heavy vehicles but also light, in addition to battery technology. There is also no evaluation of the role e-motorcycles/scooters can play in reducing emissions.”

It believes discussion of ICE bans is premature if synthetic fuel can be produced. It suggests the country should invest in the production of such ‘e-fuels’ “and we have an opportunity to do so.

“For example, once the extension to the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter contract has run its term in 2024 then that electricity could be utilised to make e-fuel to lower emissions of the entire NZ fleet of light and heavy vehicles.”

It also moots the use of wind turbines to assist in the creation of hydrogen, a process which is already signed off for trial, and is excited by the development of second generation biofuels which are sourced from various bio-stock (wood, for one) to make a crude bio-oil from which petrol and diesel can be produced.

In a recent commentary, Crawford noted “these second generation biofuels are known as ‘drop-in’ fuels which are 100 percent compatible with existing ICE engines and fuel management systems.”

Geographic isolation is among factors that have kept New Zealand from poor air quality being a regular experience in our big cities, however motor vehicles are a major contributor, hence why CO2 count enforcement is important.

WE’VE been tardy about creating an emissions standard, but finally something is being done.

The clean car import standard laid out on January 28 sets an average emissions target of 105 grams per kilometre and follows a swift timeline; legislation will be progressed this year and a standard will be in place in 2022.

Next year the only onus is on distributors of new vehicles and importers of ex-overseas’ used (and parallel imported new) cars is to report CO2 data. From 2023, penalty will begin to apply to any player who fails to meet targets.

These will start at $50 for every exceeded gram, rising to $75 per gram in 2025. Used car importers will be charged half this amount. In 2025 there’ll be a review. An even lower emissions target could very well result. The European Union already has a target of 95g/km.

It’s a grand plan, and perhaps you’re still struggling with understanding how it might affect you. Certainly, the industry has views, too, and today’s piece results from discussion with numerous figures within that business, to get a handle on what they are thinking.

And one point before going further. Though it has cautioned this is an especially steep challenge to meet Government’s expectation within the cited timeframe, the Motor Industry Association, which speaks for distributors, is supportive of Green motoring initiatives.

This, after all, is why all the key makers have already committed to electric and, in some cases, hydrogen fuel cell. It’s their future. The biggest concern is the timeframe: We’re not necessarily taking on too much, but the rollout might be too fast.

Why the standard?

The Government cites the average vehicle in New Zealand as having CO2 emissions of around 171 grams per kilometre (g/km). It says our cars and SUVs alone average 161 g/km, compared to 105 g/km in Europe.

It suggests that, in 2017, the most efficient vehicle models on our market had, on average, 21 percent higher emissions than their counterpart models in the United Kingdom.

The industry involvers spoken to generally opined that the comparison that created this data was overly simplistic, but they all agreed the sentiment is correct. There’s concession, too, that NZ likely has less fuel-efficient cars than many markets, mainly because fuel is cheap and we don’t tend to like driving under-powered cars.

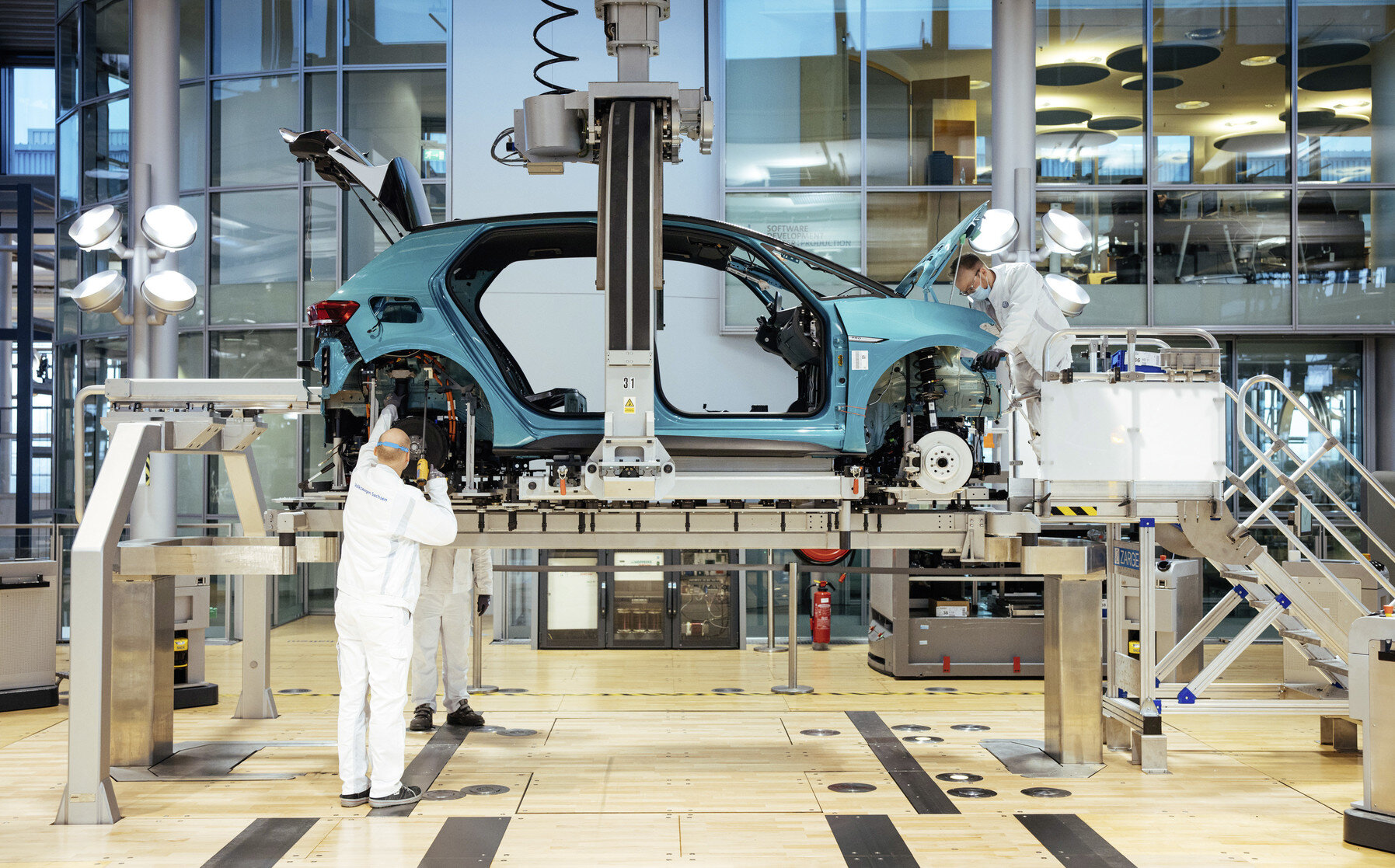

Emissions testing is serious business in many countries. We’ve not bothered.

In respect to the national output, NZ is slightly ahead of Australia, primarily due to our higher electric vehicle uptake per head of population. There’s reminder that NZ regulations insist on all new passenger product meeting at least the Euro 5 emissions standard, which dates back to 2009 and focuses mainly on reducing CO2 emissions, and some now meet Euro 6 (which dates to 2014), which reduces some pollutants by 96 percent compared to 1990s’ limits but primarily focuses on cutting diesel-associated nitrogen oxide emissions.

Commented one contributor: “Our emissions are not bad; we have better standards (Euro 5) than the likes of India and we have some Euro 6 cars here because our fuel quality is so good, unlike Australia. Our vehicles aren’t necessarily all that dirty, just thirsty.”

How strong is the argument for change?

According to the Government, the light vehicles coming into the country are among the most fuel inefficient, and emission intensive, of any OECD country.

The Government consistently cites New Zealand as being only one of two countries in the OECD without a vehicle CO2 standard. The other nation it cites is Russia. That’s not a good example. Last time we checked, Russia is not, and has never been, in the OECD.

The Government also says the target set for 2025 was already achieved by Japan in 2014 and by Europe in 2020.

The industry reminds that the latter is a bit disingenuous; it says the vehicle industry performers in Europe have not actually hit the mark; the average for 2020 has not been published yet, but in 2018 and 2019 it was 121 and 122 (yes, it went up) grams per kilometre. There is expectation that it won’t be unanimously achieved. Same goes for this year; some brands are steeling for being hit big in the pocket.

Makers are trying. The production and availability of low-CO2 product, particularly electrics, has rocketed – and they are popular, take-up being fuelled by incentives. Most countries in Europe also have fuel economy standards and high-emitting vehicles are subject to higher tax loading.

Is this just some Government plot to force us into hybrids, mains-replenished plug-in hybrid and full electric vehicles?

The Government says on average, New Zealanders pay 65 percent more in annual vehicle fuel costs than people in the European Union, even though Europe’s petrol prices are higher.

Reality is that Government hardly needs to force change; it’s coming ready or not.

Most car makers have decided to wean out of wholly fossil fuelled products and some have made quite radical commitments.

General Motors, perhaps not the best example with Holden now defunct, has decided to phase out vehicles using combustion engines by 2035. It’s pinning hope on electric (and will have 30 pure battery models out by 2025) and fuel cells. On February 7, Ford announced intent to commit $US29 billion to electric and self-driving cars. Toyota, already the world’s top gun by far in the hybrid sector, also sees itself heading in the same route; again, it sees big merit with hydrogen, but alongside electric solutions. Stellantis, the new co-op between France’s PSA and Fiat-Chrysler, is the same. Mercedes, BMW, Audi – in fact all of VW Group – Nissan and so on. And so on. All are looking to battery-enabled motoring.

However, the Government is jumping the gun if it imagines all brands have non-fossil fuelled solutions for all situations right now. This decade is very much a period of transition.

Toyota is the world’s biggest producer of hybrid cars, has the world’s biggest selection and the Prius is the world’s most popular petrol electric. However, hybrids still account for just of the make’s production.

EV production is ramping up and will continue to do so annually. Production of PHEVs is also increasing and it’s the same with hybrids. Yet overall, these do not account for a huge percentage of annual global vehicle manufacture. As much as Tesla is leading the way, it still only produced 500,000 vehicles last year. That didn’t even get it into the top 10 of global light car manufacturers.

Toyota and premium affiliate Lexus have hybrid in most of their models now; those brands have together put 15 million cars with this tech on the road since the original Prius emerged in 1997. The technology has reduced CO2 emissions by more than 120 million tonnes worldwide to date compared to sales of equivalent petrol vehicles. Great work, but hybrids still only account for 52 percent of total Toyota annual production.

The EU gave car makers 10 years’ prior warning of its expectation and, even so, that was barely enough time to develop and produce the right kind of cars. Remember, in 2011, electrics were still a novelty, there was barely any infrastructure to support them and range was poor. All that’s changed.

Europe is a core car market; because of that, and because of the CO2 penalties, it’s become a priority market for EV suppliers.

At present, most Euro EV action is contained to the premium market. The challenges are at the affordable end. Before Government’s intent was clarified, the Euro with potential to best shake up our mainstream EV choices, Volkswagen Group, was also putting us low on the shipping list.

At one time, the new-generation VW, Skoda, SEAT and Audi products on the electric-dedicated MEB platform were set to roll in from this year; now entry in late 2022 seems a best – and even that’s optimistic.

Says one involver whose brand sells fully electric and electric-assisted product. “It’s all about getting the right cars … at the moment, Europe is accounting for most (of his brand’s) production. Supply for us is not as good as we want; we take everything we can get – and can sell it – but we cannot get enough and that’s unlikely to change for years.”

FYI: The Climate Change Commission report proposing future trends reckons just 40 percent of our fleet will have electric assist by 2035.

Okay, so how will this scheme work?

ANSWER: Each supplier will have a different target to meet, reflecting its fleet of vehicles. Across the vehicles it brings in it has to ensure the average CO2 emissions are equal to, or less than, the target for its vehicles.

As it works by averaging, vehicles exceeding the CO2 target can continue to be brought in so long as they are offset by enough zero and low emission vehicles.

The 2025 target will be phased in through annual targets that get progressively lower. This gives vehicle suppliers time to adjust and source enough clean vehicles to meet the targets and to encourage buyers to opt for low emission vehicles.

These penalties – won’t they just be passed onto the consumer; meaning cars will get more expensive?

No-one’s offering any comment on this, though several people spoken to reminded that, at present, the average CO2 count is 65g/km above target. Translate that into initial penalty dollars and it represents as an average $3500 impost on stickers.

Will distributors have any support?

ANSWER: Waka Kotahi will develop an online tracking and forecasting tool to allow importers to see how their CO2 accounts would be affected if they purchase particular vehicles in international auctions. It would also help importers complying on a fleet-basis by easily allowing them to monitor how their actual average fleet CO2 emissions are tracking, against their fleet targets.

Flexibility will be given for the industry by allowing them to bank, borrow and transfer. Banking will allow suppliers to carry over any overachievement of their CO2 targets to offset the following three years.

Borrowing allows suppliers to miss their targets for one year as long as they make it up the following year.

Transferring allows suppliers to transfer overachievement of their CO2 target to one or more other suppliers operating within the same compliance regime.

That’s all well and good, says one commentator, but he remains convinced that the best incentive is … well, incentives.

That’s been proven time again overseas. More than 30 countries have EV incentives and these commonly take form of comprehensive electrification strategies, not just handouts.

“Our products are popular, but they aren’t the most popular vehicles we sell. We always ask ‘will customers automatically want to buy them’. You have to pay more for electric, that’s just an unavoidable. Some people are keen, not everyone is. The economies (of widespread acceptance) won’t work without support.”

How easy will it be for all distributors to meet the new standard – might we see some brands or vehicles, even vehicle types, simply disappear?

The Government does not address this but some in the industry would not be surprised if this scenario plays out.

Kiwis love their diesel utilities - but the type are high CO2 emitters. That’s a factor brands that do well with those models will have to consider now.

The easiest way to get the make-wide average CO2 down is to slot in an electric-assisted model into the range. EVs are of course best, because it’s only CO2 out from the vehicle: For those cars, that count is ‘zero.’

All well and good, but some makes simply do not have that luxury. The idea is for them to buy credits from those do, and have some to spare. Tesla has effectively come into profit on Fiat-Chrysler payments.

It’s not fair to name names, but it’s easy enough to find out which brands have EV strategies and which do not. Those without will be hurt.

One comment: “It’s not just the obvious gas guzzlers that are impacted by this. The requirement is for even small cars to improve and that’s a much harder ask for them than it is with big ones.”

The impact on the current fleet will be interesting, we were told. “More consumers will start to look at fuel economy.”

If this all about improving our environment, why aren’t used importers having to follow the same regime as new vehicle distributors? After all, we’re all breathing the same air. Also, there’s no mention of importers of effectively brand-new cars from overseas – what’s their responsibility?

The average ago of used imports is 10 years. The effective requirement is for these to meet Euro 5; a standard implemented 12 years ago.

So, theoretically, imports will be within this mandate. All the same, the used importers’ association, which was not approached for comment, has already expressed distaste for the requirement.

The feeling, from the new car industry, seems to be that everyone should do their share. Thought that importers of as-new product might only have to pay half the penalty the same vehicle, if over the limit, would be hit with is not welcomed. On the other hand, there’s also sentiment that those operators shouldn’t achieve any incentives, should these materialise, for favoured models. The reason? Those operators have not invested in the infrastructure required to support those cars.

Are the penalties stiff enough?

The reason why brands selling in the EU are so compelled to meet the target there is that the penalty is much steeper than it will be here; $160 per gram exceeded.

The Government says this will impact on vehicles being delivered from a certain date – it won’t be retrospective, so what we are driving now won’t be affected. Or will it? What impacts could this have on, say, on residual values – will some cars become unsaleable and, if so, what types might raise a red flag?

It’s too soon to tell. However, the potential for this legislation to change vehicle buying seems obvious.

Said one respondent: “Our cars are heavier on average than those sold in Europe. This has a massive impact on fuel economy. The best way to get average economy counts down is to drive more efficient cars.”

At the moment, some said, we have cheap fuel and use too much of it. “We love powerful and large vehicles, and 23 percent of new vehicles sold are utes, which on average are all emitting more than 200 grams of CO2.

“That factor alone makes us very different to Europe. Utes aren’t at all popular over there.

What drives that interest? Perceived superior versatility (which is often not realised in reality – many vans are better choices), opportunity to circumvent Fringe Benefit Tax and our love of towing.

The whole swing to utes has rankled some. One thought expressed: “The high level of ute uptake by businesses is a direct result of the Inland Revenue Department’s failure to police their FBT rules.

“Check out your local boat ramp and I bet you’ll see plenty of sign-written utes and just know their owners aren’t paying FBT, though they should be.”

Electric car uptake is set to rise, but no simply because of political will. Fact is, most carmakers now see this technology being their future.

Beyond that? “The older and thirstier – and that’s not necessarily the same thing – vehicles will become less popular,” one involver suggested.

“If the cost of carbon continues to rise, and we can expect this, fuel will get more expensive and interest in thirsty cars will continue to decline … hopefully this will be supported by a scrappage scheme.”

And potential red flags? A hard one, but potentially ultimately anything with a six or eight-cylinder petrol engine that isn’t considered a classic. Perhaps some turbocharged four-cylinder mainstream cars.

Are there any circumstances where vehicles might be subject to dispensation; we hear that in the EU, all the really exotic stuff – you, know, your Ferraris, McLarens and Rolls-Royces and so on – are exempt because their production runs are so low. Will that happen here, do we know if there is a registration count cut-off for what excludes and what doesn’t?

The exemptions so far explained are for: vehicles intended primarily for military operational purposes; agricultural vehicles/equipment that are primarily driven on farms, such as tractors, harvesters, mowers, toppers, bailers; vehicles with historic value, or vehicles such as classic cars; motor vehicles constructed before 1 January 1919; motor vehicles constructed on or after 1 January 1919 and are at least 40 years old on the date that they were registered, reregistered, or licensed and scratch-built vehicles and modified vehicles certified by the Low Volume Vehicle Technical Association.

It’s still unclear if that same leniencies that have allowed the high-end exotic brands to keep selling in the EU will impact here. However, it is worth noting that many are intensifying the electric efforts nonetheless. Though, in the case of Rolls-Royce, the potential of a fully electric car before too long has nothing to do with consumer demand. It’s more because big cities around the world are increasingly deciding to shut themselves off the high-emissions traffic.

Anything else we need to know?

Australia.

We historically often collude with our neighbour on common market selections. Car makers love volume. NZ doesn’t buy many new cars but, if we take the same stock as our neighbour, then often it’s enough to win a production priority and a stronger negotiating status.

Our tastes were already distancing but the new legislation might lead to a complete divorce. Our respective national visions are far from alike.

Australia has no mandated CO2 regulation now and, more disturbingly, is disinclined to adopt one; a situation that in itself has so alarmed the car industry they’ve rolled out a voluntary code.

Even then, they face a different core challenge. A catalyst for our neighbour’s relatively lax emissions regs is that the fuel sold there is of lower quality than we receive. This means Australia’s fuel and Euro 5-based noxious emissions standards are lax by global standard; to the point where they act as an impediment to introduction there of internal combustion engines that can be sold here. The standards are being tightened. But not until 2027.

Like us, they’ve ruled out EV subsidies in favour of encouraging companies to electrify their vehicle fleets. We aim to make EV owners pay Road User Taxes (though when is still unclear). Over there, some states are pushing for EV road taxes to compensate for lost fuel excise earnings; Victoria is considering fiting EVs with GPS trackers for per kilometre charging. Why would anyone keen to kick the oil habit been keen on that?

Beyond that, Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s administration seems largely indifferent to the matters we are aiming to address.

The Federal Government seems to be happy with indulging in what a senior writer with Wheels magazine has called an “embarrassing fossil fuel addiction while the rest of the world joins the e-volution.”

Daniel Gardner, who said his views about electric cars and the positives of their involvement in any roadscape came from (pre-Covid) visits to Europe, particularly time spent in Germany, says he is embarrassed that the Australian Federal Government's 2020/2021 Federal Budget included money to upgrade a coal-fired power station in New South Wales, and $A52.9 million expanding Australia’s gas industry “while allocating a measly A$5 million for electric vehicles.”

He added: “Get chatting to a German and, regardless of their political inclination, they simply won’t believe why we are so opposed to electric vehicles and gorging ourselves on fossil fuels. And when you see just how feasible Germany makes the transition to electric cars appear, you probably wouldn’t either.”

Australia’s determination to keep mining and burning coal relates so much about our neighbour’s attitude toward clean air concern, critics say. EV producers’ making Australia a low-priority market might not do un any favours.

He wrote of exasperation that “Australia has a government that sees absolutely nothing wrong with digging millions of tons of filthy brown coal out of the ground and burning it to power the nation. A government that not only refuses to invest in renewable energy despite being one of the most suitable countries in the world, and instead favours more coal mines.

Australia’s indifference has also fired up the country’s peak electric vehicle lobby, which says the latest future fuels strategy, which released in draft form late last year, as “yet another flaccid, do-nothing document that will prevent Australians getting access to the world’s best electric vehicles”.

They’re right. Limited electrified vehicle production is being allocated to places where incentives are greatest and/or restrictions on CO2 are the most painful. Australia? Said Wheels magazine last month: “As the Federal Government’s ideological constraints and contradictions extend its environmental and electric vehicle policy vacuum, Australia is slipping down the shipping list.”

NZ distributors are finding themselves having to negotiate directly with makers to achieve any kind of product and often there’s a cost – which has to ultimately be passed on – and, in many cases, acceptance of compromise (so, a car might arrive in another right-drive country’s spec: Latterly, it’s been Ireland).

Having a neighbour we can’t live with, but cannot live without is hardly helpful.

Diesel utes are No.1 with Kiwis …. but they’re not going to make the clean air cut.

BASICALLY, we don't like our 'greens' and consume too many meaty products.

That’s the national new vehicle buying pattern in a nutshell.

Sports utilities, crossovers and, in particular, one tonne utilities. These are the vehicles we love the most; to the point where they cumulatively outsell conventional cars and the Ford Ranger has become the country’s best-selling model.

Great stuff. Just one wee catch. It’s always been common knowledge that, were New Zealand ever to get its act together and implement some kind of emissions regulation, then the vehicles Kiwi love most would get us into trouble.

CO2 emissions from new passenger and light vehicles have been declining. However, our national average is well above where the Government has now decided it needs to be; mainly because we’ve been making too many dirty decisions.

Core to announcement yesterday of a Clean Air Standard is intention to reach a CO2 target of 102g/km by 2025.

Easy-peasy? The current NZ average for cars and SUVs is 161g; overall, the fleet is around 171g – an improvement on a year ago, if only by 3g. And today’s average is still below is still slightly below the target the European Union set for its territory in 2003.

So, yeah, the challenge is to achieve a reduction of almost 40 percent from the current new-vehicle average. Utes, which are particular grubs, and vans must hit 132g in the same timeframe.

There’s no time to waste. The Government intends to pass the law this year and enact the standard in 2022, with the first charges being levied on any who miss their annually reducing targets from 2023.

It’s not as if we didn’t know this day was coming. Fact is, NZ is just catching up to a world trend, which in a way is going to be helpful.

Vehicle makers are already being compelled the same targets in much larger, more crucial markets; their reaction to that challenge means they are already making products that are in step with the NZ intention. We will get many of those vehicles.

The European Union mandate on makers selling in its territory to meet an even higher standard, a fleet-wide average of 95g/km, and Japan’s mandate for a 104g/km standard, are especially compelling. Vehicles tailored to meet or exceed those expectations will also come here.

The NZ model is not too different from the EU’s. Vehicle suppliers will have different targets to meet, and will only have to ensure that the average efficiency of the cars imported in any given year meets the standard. This means higher-emission vehicles can still be imported but will have to be offset by cleaner vehicles.

Failure to comply will be penalised, as in the EU, but not to anything like the same extreme. In the EU, fines can be large enough to bring a brand to its knees. Here a penalty will be applied from 2023 of $50 per gram of CO2 above the target for new vehicle imports or $25 per gram above the target for used vehicle imports - but it is applied across the fleet.

If you decided, today, to investigate which vehicles on sale at this very moment were already meeting that new cut-off … well, the shortlist would be very short indeed.

even acknowledged thrift-meisters such as the top-selling Suzuki Swift are challenged to meet the 105g/km standard. The hybrid version, above, does with a count of 94g/km but conventionally-powered editions do not.

Forget conventional internal combustion-engined cars; even especially thrifty types struggle to be that clean.

You need to go hybrid, though even then it’s not a given. Toyota's Prius, Yaris, C-HR and Corolla petrol-electric models are all under the 105g/km. The Camry hybrid and the hot-selling RAV4 hybrid are on the wrong side of the fence.

The models that will make more of a difference are will be used by brands that can achieve them to lower their fleet averages are, of course, plug-in hybrid (PHEV) and fully electric vehicles.

This has been shown in the EU, where makers were generally starting from a base of 120g/km.

These are vehicles that, of course, many big players are now making in greater volumes. Ironically, some have been hard to secure for NZ because their makers are prioritising places where they have to represent electric fare or face fines – this is why VW Group product has been restricted, or completely held back, from NZ introduction. Europe’s biggest maker is focussing, out of necessity, on keeping those cars in EU markets. The NZ decision could well be a very useful tool for the brands’ NZ agent to now argue for prioritisation.

In the here and now, the current hybrid and plug in hybrid fare that meets or improves on the standard comprise seven BMWs, two Hyundais, two Kias, a Range Rover, two Lexus models, four Mercedes, a MINI, a Mitsubishi, a Peugeot, two Porsches, six Toyotas and four Volvos.

In addition, 14 fully electric passenger models avail here, from Audi, BMW, Hyundai, Jaguar, Kia, Mercedes, MG, MINI, Nissan, Renault and Tesla. One or two examples of the Volkswagen e-Golf might also be unspoken for, though car is not out of production and supply has ended.

The probability of seeing more electrics, PHEVs and hybrids is high – being, then, it already was anyway because, well, you might recall the motoring world is going that way regardless of how much you love your V8s.

Of course, not all brands have the luxury of being about to take the electric path. Subaru and Suzuki are barely in the game, with just mild hybrid options. No ute here yet has any kind of battery-assisted drivetrain, though a hybrid Toyota Hilux is promised and Mitsubishi has hinted at a battery-assisted powertrain for Triton. Look at Isuzu: It makes a ute and a spin-off SUV. Both rely purely on a diesel engine whose emissions are well about the new mandate.

plug-in hybrid and fully electric technology is an obvious solution to achieving or surpassing the new standard. Many brands are one step ahead … the PHEV Ford Transit is among models intended for NZ introduction.

What habits might we have to change or even quit? A year ago I wrote a backgrounder for a national publication that aimed to give insight into the vehicles that might well become problematic were our country to ever consider the CO2 issue.

That piece pointed out how our huge move toward ute ownership has been detrimental to bringing emissions down. It pointed out, for instance, that a the start of 2020, the Ford Ranger, which at that point had dominated ute sales for five years (and would do the same last year), was both a relative saint and a sinner, in that one engine it ran - the 2.2-litre four-cylinder biturbo, emitted a category best 177g/km - whereas the other, the five-cylinder 3.2-litre single turbo it launched with, evidenced a near class-worst 234.

America's big lugger RAM was also in the black. It’s XL-sized products delivered a 283.8g/km average outcome.

One solace for ute faithful now, as then, is that makes reserved for rich listers top the scale of shame. In the data used for last year’s story, Aston Martin achieved an average of 265.1 g/km, Bentley 274.7, Ferrari 279.8, Lamborghini 305.2 and McLaren 257.3. Rolls-Royce was the worst emitter, with an average of 343.3g/km.

Notwithstanding that some of those makes are now fast-tracking into an electric age, it’s probable more of those cars are going to come under the spotlight. Some might be withdrawn, others will asuuredly become even more expensive as penalties are passed on to the customer.

Spencer Morris with the updated catalytic reduction system and particulate filter that will not only feature on the impending 2020 Hilux, Fortuner and Prado but will also become a retrofit for pre-face NZ-new examples of those models.

NO more white smoke, no longer a risk of a blackened reputation – that’s the expected outcome of a fix for an engine powering Toyota’s recreational and utility vehicle push.

Toyota New Zealand is confident the refreshed version of the 2.8-litre four-cylinder turbo diesel progressively rolling out over the next few months – initially in the upgraded Hilux on sale imminently then its sports utility sibling, the Fortuner, and lastly the LandCruiser Prado - has reconciled an emissions technology failing that has affected examples of those models for some years.

A remedy that has been on trial here since last year is good news for those customers who own pre-facelift examples of those cited vehicles, too, as the brand intends to retrofit these with the fix, as well.

Optimism voiced by the Palmerston North-headquartered brand’s technology expert and after-sales manager, Spencer Morris, that problems with the engine’s catalytic reduction system and the diesel particulate filter (DPF) intrinsic to its operation have finally been nailed has come along with frank discussion about how much time and effort – primarily here, ultimately in Japan - has gone into reconciling an issue that might have caused customer disquiet.

the updqted hilux, now just weeks from going on sale, will be first to debut the big fix.

“It’s been a complex problem to solve,” Morris acknowledged.

“It has not been easy for us. We have had a number of Japanese visitors out to assess the issue and have had quite hard conversations about how to get on top of this.

“Every time we did something (remedial) the fail rate went down, but we never got a 100 percent cure until now, with a new DPF.”

Fitted between the engine and exhaust, DPFs collect soot and dangerous particles from diesel.

Because DPFS, like any filter, only have a certain capacity the captured pollutants – some carcinogenic (meaning they can cause cancer) – have to be burned off, a process called regeneration.

All going well, the system will reduce particulate emissions by around 80 percent compared with your diesel-powered vehicle not having one, but the process requires the engine reaching a certain temperature and maintain it for the period of regeneration.

The system previously used by the 1GD-FTV 2.8-litre from 2015 until now has proven problematic in its original design, though curiously just within Australasia.

In saying that, while around 2000 New Zealand-new vehicles have returned issues, our market has come off lightly compared to how our neighbour appears to have fared.

The total count of vehicles showing issues here represents just 10 percent of total Hilux, Fortuner and Prado volume achieved over the past five years.

This suggests a much lower impact than is reported in Australia, where the issue has triggered a class action lawsuit, yet to be reconciled, on behalf of angry owners.

For its part, TNZ has determined to be highly proactive – not only will the updated models of the affected product have a new combined DPF and catalytic converter that provides resolution, but that part is also to be issued as a retrofit to all the vehicles it sold within the time frame where it has potential to become an issue.

“Now we have a fix our intention to over time replace all of them. Our priority (to date) has been problem vehicles and we have pretty much worked through them.”

The redesigned DPF that Toyota Japan has created for the updated models coming soon has been trialled here since last year.

“We have fitted it to the very worst affected vehicles since last year that we couldn’t (previously) fix and it has provided a satisfactory fix … we’re very happy with the outcome and, more importantly, the customers were happy with the outcome.”

Morris reinforced that TNZ always took the issue seriously and was absolutely committed to finding a resolution as customer satisfaction was always the highest priority.

“We replaced some vehicles because we inconvenienced some customers so much. We had a number of attempts of fixing their vehicles and, in the end, we said ‘we have mucked you around too much.’ So the conversation went down the route of replacing.”

updated Prado is also due to take the refreshed technology.

What might have saved us could be the weather: Simply, the hotter the climate, the worse the problem seems to be. Also, it seemed less prevalent on automatics than the manual.

Says Morris: “From what I understand, this was not a global problem. It was very much our markets.

“Ambient temperature is an issue … we have certainly not seen it as a nationwide issue. The further north you go, the worse it seems to get.”

However, it’s not the sole factor for failure. Another is a common challenge for all diesel powertrains with DPFs struggle to cope with: Long-term idling and vehicles being driven short distances and at low speeds also accelerated the build-up of particulate matter.

Either way, the Toyota problem at its worst was impossible to ignore; blockages and the tell-tales of foul-smelling emissions from the exhaust, poor fuel economy and greater wear and tear on the engine – culminating in copious output of white smoke from the exhaust.

Toyota’s first try to get on top of this was an update to the engine software, the introduction of a DPF custom mode, and a manual inspection of the DPF for built-up particulate matter.

When that didn’t deliver as hoped, the factory stepped up to adding, in 2018, a button on the dashboard for owners to be able to manually regenerate the system if it was not automatically doing so at the required moment.

This button remains as a fully factory-fitted item in the 2020 models, which also gain more specific software and hardware improvements that, the make says, further improve the way the DPF operate and how it regenerates.

The button is a good back-up to the vehicle’s regenerative programming. “Automatic regeneration happens when the system determines it needs to be done, but it has to complete the cycle.

Some operators found that was an inconvenience, because the process requires a period of time to complete. The manual control therefore was better for them.

“If you’re operating in an environment where you don’t want it to regenerate during that time, you might prefer to action that process in a more convenient place.

“But I don’t know if our issue was entirely about just the regeneration, because it’s not just a DPF – that’s all part of a catalytic reduction system and it also requires a diesel oxidation catalyst, a catalytic converter.

“The DPF and catalyst are one unit. Exhaust gas passes through the catalytic converter first and then the soot is captured in the DPF.

“There are a number of different system designs but what you’re basically trying to do is poke fuel into the exhaust and get that to do the burning.

“You can do it in a number of different ways. One that is not uncommon is to inject fuel on the exhaust cycle, so you’re not combusting it, but putting it down the exhaust pipe.

“That’s problematic because it can also cause your oil to be diluted, and some brands have had that problem. We have had it in the past, on some used import vehicles.

“The Hilux uses a system that injects fuel directly into the manifold, using a fifth injector, and one of the problems we were having was seeing a certain amount of blockage in the oxidation catalyst.

“That caused white smoke and is what Hilux became known for.”

How to fix this? That was a frustration.

“We had a number of counter-measures … we tried a number of remedies along the way, all of which we thought would work … but they worked for some cases, but not for others.

“Our fault rate diminished over time, but we didn’t have a complete fix, so we weren’t able to satisfy all customers. It was frustrating for them and for us.”

But, finally, a breakthrough. “We are pretty confident now we have solved the problem.”

The end cost in dollars? Morris has no idea, but imagines it wouldn’t be paltry.

“It has been an expensive exercise but we’re all about ensuring people have a great customer experience. We regret that some people have not had a great experience in this case, but we have never given up.

“We have worked on solving the problem and stuck at it until it has been resolved.”

Meantime, as well as a resolution to this issue, the 2020 update powertrain also delivers a performance upgrade, with the engine now producing 150kW at 3400rpm and 500Nm at 1600-2800rpm when mated to the automatic transmission, whereas the manual transmission option develops a lesser 420Nm at 1400-3400rpm.

MotoringNZ reviews new cars and keeps readers up-to-date with the latest developments on the auto industry. All the major brands are represented. The site is owned and edited by New Zealand motoring journalist Richard Bosselman.